Comments on Berkshire Hathaway and its annual meeting

I attended the Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B) annual meeting on Saturday – my 23rd in a row (21 in-person and the past two virtual). I can't wait to return to Omaha, Nebraska, for future meetings (put April 30, 2022, on your calendar)!

Yahoo Finance livestreamed the meeting (plus the pre- and post-meeting shows, during which I was a guest) and posted the entire five-hour-and-42-minute video of it on YouTube here (I recommend watching at 2-times speed).

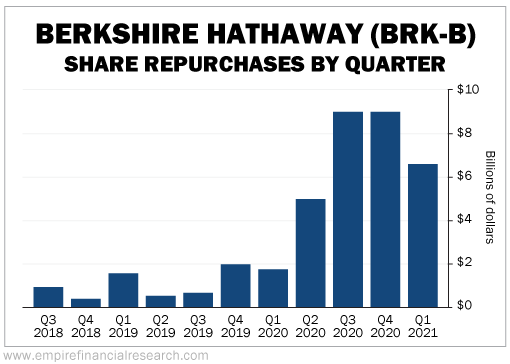

During my comments before the meeting (starting at 1:06:19 in the video), I highlighted Berkshire's substantial share repurchases over the past year, which have reduced the share count by 5.5% year over year. Yahoo showed this chart that I created highlighting how much Berkshire has spent on repurchases each quarter since its buyback program began:

I then shared my latest estimate of Berkshire's intrinsic value, updated to reflect the first-quarter earnings that the company reported on Saturday.

I've used a consistent and simple methodology – one that I think CEO Warren Buffett himself uses – to value Berkshire for more than two decades: Take cash and investments (valued at market) and add the value of the wholly owned operating businesses, calculated by applying a conservative multiple (I use 11 times) to the pre-tax earnings of those businesses.

This table shows how I calculate Berkshire's investments per share:

Adjusting the stock portfolio upward by the 5.3% increase in the S&P 500 Index during the month results in investments per share of $312,000 as of the end of April.

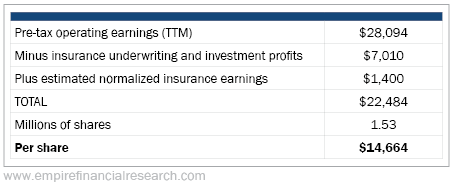

To value the wholly owned businesses, here are the figures I use to calculate their earnings:

Note that I subtract all of the underwriting and investment profits from Berkshire's massive insurance operations, but add back a rough estimate of the average insurance underwriting profits over the past decade ($1.4 billion annually).

This results in $14,664 in trailing 12-month adjusted pre-tax earnings per share, to which I apply a multiple of 11 times to arrive at a value for the operating businesses of $161,300 per share.

Now add the $312,400 in cash and investments per share to arrive at a total intrinsic value of $473,700 per A-share (or $316 per B-share).

With the A-shares closing Friday at $412,500, that means the stock is trading 13% below my estimate of its intrinsic value.

During my comments after the meeting (starting at 5:15:03 in the video), I started by saying I was "in awe" that Buffett and his long-time right-hand man, Charlie Munger, are still going strong at age 90 and 97, respectively. That's particularly amazing when you consider that the life expectancy of the average American man is 79.

The biggest risk factor for Berkshire and its stock is that Buffett and Munger, as they age, start losing it mentally and make terrible investment mistakes. But I could see no sign of this... For four straight hours, without even a bathroom break, they answered dozens of questions, none of which they had advance knowledge of, without missing a beat.

In fact, if you played me an audio of Buffett and Munger at this meeting versus the first one I attended in 1999, I'm not sure I'd be able to tell the difference.

One big difference during the meeting, however, was the participation of Vice Chairmen Greg Abel and Ajit Jain, both of whom spoke a handful of times. During the meeting, Munger inadvertently revealed what was widely expected: Abel is slated to be Buffett's successor (though I don't think this transition will occur for at least five years). Here's an excerpt from a CNBC article about it:

"Greg will keep the culture," the 97-year-old Munger said simply, explaining that the company's decentralized nature would outlast him and Warren Buffett.

But that was enough to clue in some Berkshire watchers, who have been wondering about succession plans at the conglomerate once 90-year-old Chairman and CEO Buffett is no longer in charge. To many, it signaled the top job will go to Vice Chairman Greg Abel, who runs all of the noninsurance operations.

The impression was an accurate one, CNBC can confirm.

"The directors are in agreement that if something were to happen to me tonight, it would be Greg who'd take over tomorrow morning," Buffett said…

"If, heaven forbid, anything happened to Greg tonight then it would be Ajit," said Buffett, adding that age is a determining factor for the board. Abel is 59 and Jain is 69. "They're both wonderful guys. The likelihood of someone having a 20-year runway though makes a real difference."

When asked about criticism (including some from me!) that Buffett made a big mistake in selling airline and bank stocks last year, I acknowledged that this cost Berkshire $15 billion (an estimated $5 billion and $10 billion, respectively) and noted that a younger Buffett might not have made this mistake.

But I also argued that a younger Buffett eschewed all tech stocks, so he wouldn't have owned Apple (AAPL), on which Berkshire has made over $100 billion in profit – so shareholders should be delighted to make that trade all day long!

I also rebutted those who've criticized Buffett for selling some of his Apple position. Rather than lamenting that he left a little money on the table by selling a small portion of this stake, shareholders should be thankful that he's held onto the rest of it.

One of the biggest mistakes I made over and over again in my career was selling my winners – like Apple, Amazon (AMZN), Netflix (NFLX), Ross Stores (ROST), Home Depot (HD), and McDonald's (MCD) – far too early. Buffett, in contrast, has done a phenomenal job of letting his winners run.

I chuckled at how history always seems to repeat itself... At the first Berkshire meetings I attended in 1999 and 2000, tech stocks were flying and naïve individual investors were piling into the market. While many commentators at the time were dismissing Buffett and Munger as out-of-touch old fuddy-duddies, I was shouting from the rooftops that we should all be listening to them.

Sound familiar?

Just as they did back then, on Saturday Buffett and Munger heaped scorn on the latest fads and bubbles like bitcoin, trading apps like Robinhood, and questionable special purpose acquisition companies ("SPACs") that are sucking in the next generation of retail investors.

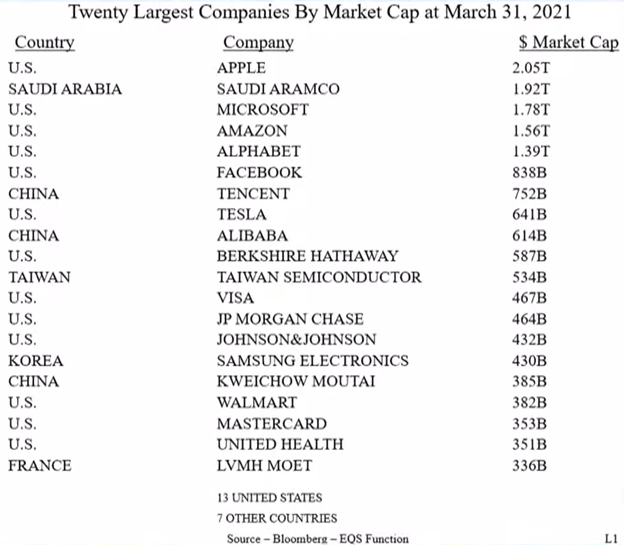

Buffett even prepared a slide showing the 20 companies worldwide with the largest market capitalizations today:

He then showed the same list from 32 years ago in 1989:

Buffett pointed out that not one company made both lists – underscoring (though he didn't exactly say this) that the most popular stocks generally don't make good investments in the long run. He also noted that Japanese companies occupied 13 of the top 20 spots in 1989 versus none today. In fact, the largest Japanese company today, Toyota Motor (TM), is No. 46.

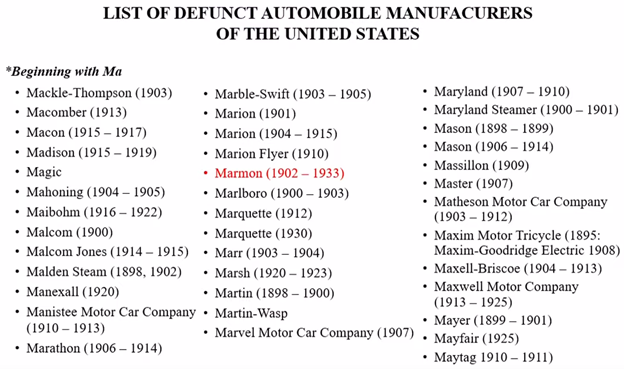

At another point in the meeting, Buffett warned that investing in new, exciting, high-growth industries can end very badly, using automobiles as an example. Autos started to go mainstream beginning a little more than a century ago and they undoubtedly changed the world – but investing in this sector was catastrophic, as there were only a few survivors among the more than 2,000 auto manufacturers that once existed. He showed this list of just those with names starting with "Ma":

My final comment was about Buffett and Munger's humility. To be a successful investor, you need to be both arrogant – thinking you have an important insight that's different from the consensus view – but also humble – recognizing that the crowd is usually right and/or that you have no expertise in most areas.

Nobody could have predicted the events of the past year – and nobody today can say with certainty what will happen going forward – though a lot of people try. But Buffett and Munger don't...

As rich, successful, and acclaimed as they are, they don't let their egos lead them down rabbit holes. They keep their heads down, focus on what they know and what they're good at, and don't spend one moment thinking about things like the possible consequences of unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus or the fact that others are making fortunes in cryptocurrencies.

Lastly, I didn't have the chance to comment on whether Berkshire can endure for another 50 years. When Buffett and Munger were asked about this, they were optimistic, citing Berkshire's unique, decentralized culture. Munger compared it to the Roman Empire, which lasted so long due to decentralization, and talked about Berkshire lasting another 50 to 100 years. I agree!

Best regards,

Whitney