Netflix Prepares to Send Its Final Red Envelope; Advice I gave to Reed Hastings; I met Ukraine expert Malcolm Nance

1) In yesterday's e-mail, I shared two examples of similar advice I gave to the management teams of cannabis company Tilray Brands (TLRY) and 3D printer manufacturer voxeljet (VJET) when their stocks became massively overvalued.

This article on the front page of the business section of today's New York Times reminded me of another story I've never shared about the advice I gave the then-CEO of Netflix (NFLX), Reed Hastings, a dozen years ago: Netflix Prepares to Send Its Final Red Envelope. Excerpt:

In a nondescript office park minutes from Disneyland sits a nondescript warehouse. Inside this nameless, faceless building, an era is ending.

The building is a Netflix DVD distribution plant. Once a bustling ecosystem that processed 1.2 million DVDs a week, employed 50 people and generated millions of dollars in revenue, it now has just six employees left to sift through the metallic discs. And even that will cease on Friday, when Netflix officially shuts the door on its origin story and stops mailing out its trademark red envelopes.

"It's sad when you get to the end, because it's been a big part of all of our lives for so long," Hank Breeggemann, the general manager of Netflix's DVD division, said in an interview. "But everything runs its cycle. We had a great 25-year run and changed the entertainment industry, the way people viewed movies at home."

When Netflix began mailing DVDs in 1998 – the first movie shipped was Beetlejuice – no one in Hollywood expected the company to eventually upend the entire entertainment industry. It started as a brainstorm between Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph, successful businessmen looking to reinvent the DVD rental business. No due dates, no late fees, no monthly rental limits.

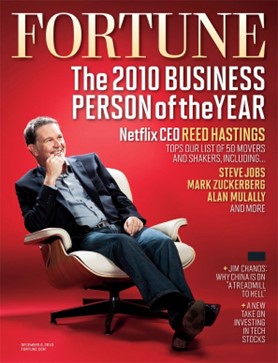

By July 2011, Netflix had soared to more than $40 per share (adjusted for a subsequent seven-for-one split), up from less than $1 per share in 2003 – making it one of the greatest growth stocks of all time. Hastings was a media darling – Fortune even named him its 2010 Business Person of the Year:

I think all of this went to Hastings' head a bit and led him to make a terrible mistake: to pursue the exciting nascent opportunity in streaming video, he decided to spin off the company's DVD-by-mail business into a separate business called Qwikster. Subscribers rebelled, furious that they would now have to sign up for two services (and pay twice).

In less than two months, Netflix fell by more than 57% to $18.36 per share, which led Hastings to send a lame "mea culpa" letter that didn't fix the problem. To help him out, I sent him this e-mail on September 22, 2011:

Reed,

Here is an article that just came out by David Pogue, the widely read and respected tech columnist for the New York Times: Parsing Netflix's 'Apology'. He concludes:

I could not have put my reaction any better than this e-mail from a reader:

Netflix's split into Qwikster is ridiculous. I wasn't mad at them before; I am now. I don't want two companies, two credit card charges, two Web sites, two logins, and TWO queues to maintain.

Now I have to add movies to both an instant and a DVD queue? I have to check both sites to see whether a film's available by instant or by DVD? I have to sync my iOS devices to two different services for instant film delivery and queue management?

This is ridiculous. Life's complicated enough already. Netflix (excuse me, "Qwikster") just made it worse. Does Mr. Hastings thinks we're idiots? Making it two companies, with two charges, doesn't change the essential price dynamics; we can add.

Netflix just violated the first principle of good business: it solved ITS problem, not ours. This is the worst American marketing decision since New Coke, and I hope it's reversed just as quickly.

I confess: I'm utterly baffled.

At why Netflix, long hailed for its masterfully gracious customer focus, has suddenly become tone-deaf to the effects of its clumsy elephant-in-a-china-shop maneuvers.

At the reasons behind all of these shenanigans. Yes, of course, fewer people use DVDs, but come on, they haven't all fallen off a cliff simultaneously.

At why Mr. Hastings thinks it helps to say "I messed up" without actually making things right. That's one of the hollowest apologies I've ever heard. It's lip service. It's like the politician who says, "I'm sorry you feel that way." You're not sorry – in fact, you're still insisting that you're right.

In the end, though, what makes me unhappiest is how calculated all of this feels. In July, a spokesman told me that Netflix had already taken the subscriber defection into account in its financial forecasts.

And sure enough. When I tweeted that Netflix had lost one million of its 25 million customers, @npe9 nailed it when he wrote:

It damages their brand and images, but 24 million customers paying $16 is still better than 25 million @ $10. Increases revenue by >50%.

Yes, Mr. Hastings, you did mess up.

Twice.

I then continued in my e-mail:

In your e-mail to me yesterday, you concluded: "it is a lot of damage we've taken." Yes, of course – but the tone of this sounds like you're in a bunker mentality and just have to weather the storm.

THIS IS BAD THINKING! There are things you can – and must – do to fix this.

After sharing the experience I was going through in my hedge fund, weathering a bad year, I wrote:

You (and your management team and board) need to be asking yourselves: "Knowing what we know now, if we could rewind the tape by a few months and do it all over again, what would we do?" Then, if the answer is anything different, ask yourself: "OK, why can't we do that now?" In other words, if you had to do it all over:

- Would you jack up the price for your DVD-by-mail service up so quickly and by so much, or would you have increased it more slowly? If the answer is the latter, then roll back, say, $4 of the $6 increase. (I'm not saying this was a mistake – perhaps it's better to rip the Band-Aid off quickly – my main point is that this decision can be reversed.)

- If you suspect that Qwikster is a dumb name, then CHANGE IT! I think it is – if you don't like Netflix Classic (which I still prefer), how about Netflix By Mail or Netflix Direct?

- If you now realize that it was a HUGE blunder to create a separate web site, with separate credit card info, queues, etc. (which it was), then RESCIND IT!

There is absolutely nothing (except your pride) to keep you from writing a second mea culpa letter, fixing your mistakes. That's what we're doing and it's no fun, but it's the only way that our investors will forgive us and give us another chance. Maybe some won't – but I know for sure that almost all of them will leave if we don't acknowledge and fix our mistakes.

I think the same is true for you, so get out of your bunker, eat some more humble pie, and fix your mistakes.

If you do, your stock is a great buy – and we'd love to make some money being LONG your stock!

Good luck!

Whitney

Soon thereafter, Hastings did as I suggested – issuing a second "mea culpa" letter and killing the Qwikster idea.

But the damage was done... A month letter, Netflix was down another 37% to $11.55 per share, which prompted me to send him this e-mail on October 27:

Hi Reed,

My hour as guest host on CNBC went well and I was able to lay out our thesis on Netflix in some detail in one segment, while also defending you in another. Here's a blurb about the second segment:

Asked in a wide-ranging interview his view of Netflix, Tilson said Chief Executive Reed Hastings of late has made errors, but that the company is on the right track in terms of profits.

Hastings is a "real visionary," said Tilson, although he has "clearly made some mistakes by his own admission" of late. He was wrong on the Qwikster fix but corrected that, said Tilson. Importantly, however, Hastings didn't back down on pricing issues, which was the right move, said Tilson. The move cost Hastings some subscribers, but that loss will stabilize, said Tilson, and Hastings will have a "higher profit company."

I enjoyed catching up with you yesterday. The only thing I want to push back on is how you view the DVD-by-mail business: I really got the sense that you view this business as a dog rather than a gem. Of course it's a dying business and the future is streaming, but it's also your cash cow and you need to milk it for all it's worth.

We've invested in declining businesses like paging companies and check printers over the years, so believe me when I tell you that, managed properly, your DVD-by-mail business should provide healthy profits for many years to come, which will provide a cushion for the stock as well as cash flow to fund growth and international expansion for streaming.

Best regards,

Whitney

In a funny addition I had forgotten about, I added this P.S. I added with an article by my then-friend and now-colleague:

P.S. I trust you saw this by Herb Greenberg who (I hope you're sitting down) actually has some nice things to say:

In Praise of Netflix CEO Reed Hastings

Published Tue, Oct 25 2011

https://www.cnbc.com/2011/10/25/in-praise-of-netflix-ceo-reed-hastings-greenberg.htmlFor most of its public life, I've given Netflix a hard time.

Although I have become persona non grata at Netflix, it has never been personal. It has always been about the stock relative to the metrics or the quality of metrics –never about the personality of the guy running the company.

I've never met CEO Reed Hastings personally, but in the company's pre-public days of the late 1990s, when I was a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, we corresponded a few times. He had this fascinating new business model – to deliver DVDs by mail – and I was raising red flags over Blockbuster.

He had a passion and drive and not-so-subtle confidence about a concept that was still largely under-the-radar. (Net-what?)

At the time we both believed Blockbuster was vulnerable, but for different reasons. I had believed the vulnerability was more at the hands of cable and movies on demand; he was one step ahead of me, during a decade-long period of transition, with DVD by mail. I never bought into the DVD by mail concept because a) I had small kids and we always went to the Blockbuster store – roaming the aisles looking for something to rent; and b) I can't predict when and what I'm going to watch on any given day, let alone days in advance. (With me, it's when the mood strikes.)

But as Hastings and Netflix proved, I was in the minority – and the business took off, becoming one of the great Silicon Valley success stories and iconic brands.

Doing what I do for a living (picking apart companies) you get to respect the challenge and difficulty and complexity of building one.

Even as I was raising red flags over Netflix's stock, I would often toss in a compliment about the execution of the strategy.

Which gets to my praise of Hastings: Away from the stock price, he did what most can't do: He built a heck of a business.

Then he fell into the classic trap of believing his own press clippings. Hastings admitted as much in September when he told subscribers, "I slid into arrogance based upon past success." Not only had he become star in Silicon Valley and an unlikely and from-out-of-nowhere powerhouse in Hollywood, but Hastings had become a hero on Wall Street. His rocketing stock became the ultimate scorecard, and it's my guess that like so many other executives, Hastings confused the stock with the company.

Hastings has since apologized multiple times for recent missteps, but the reality is this: No matter what Netflix did, it was bound to stumble. All good businesses do; it's part of risk-taking and risk-taking is required for businesses to grow.

But Netflix's success was based on the brilliant disruption of an existing, entrenched model with something consumers didn't realize they needed.

Now Netflix is just another company trying to win in the increasingly competitive, costly world of streaming. That Hastings has stumbled multiple times shows how nobody quite knows what will work or who will win.

It's just the natural evolution of a rapidly changing industry. Hastings, at this point, is just trying to figure it out like everybody else. The good news for him: With his stock pummeled, he has one less thing to worry about.

This story, of course, has a happy ending, as Netflix today sits at around $380 per share – making it (again) one of the best stocks of the past dozen years.

But it wasn't an easy journey...

Even after correctly identifying a brilliant, visionary CEO and a leading company in a massive new industry, and patiently waiting to buy the stock in late 2011 after it had fallen by 75%, I had to endure another year of pain, as the stock gyrated between $10 per share and $18 per share until it finally bottomed at $7.78 per share on October 1, 2012.

Fortunately, I hadn't lost faith – remember Warren Buffett's maxim, "Mr. Market is your servant, not your guide" – so on that very day I pitched it as my favorite stock idea to the 500 attendees of my Value Investing Congress and, immediately afterward, on national television on CNBC, saying it was this decade's Amazon (AMZN), which had risen 20-fold in the previous decade. (You can see the slides I presented here.)

It turns out I was too conservative, as Netflix rose 90-fold in the next eight years!

2) Last Friday I had the pleasure meeting one of the world's most interesting people, Malcolm Nance, on the left in this picture:

Nance's family has been in the U.S. military continuously since 1864, he served 20 years in the Navy and then 20 years afterward as a consultant, with a specialty in cryptography, intelligence, and counterterrorism. He has been to 86 countries (beating my 80!), is the author of 10 books, was MSNBC's expert on terrorism and Ukraine, and has 1.1 million followers on X (formerly Twitter).

Most important as it relates to Ukraine, Nance correctly and publicly predicted Russia's invasion and went to Ukraine beforehand, drove every one of the roads that Russian forces used, and worked with its top military leadership to develop a strategy to extend and then destroy Russia forces. Almost alone among U.S. commentators/analysts, he correctly predicted that Russia's invasion would fail.

Then, after the invasion, Nance went to Ukraine and joined the army, becoming a Legionnaire, and fought on the front lines near Kharkiv in the highly successful counteroffensive.

So he is definitely someone we should all listen to very carefully...

When I asked him how the current counteroffensive is going and prospects for the war, he replied:

Ukraine is certain to win this war. The Russian forces are poorly trained and led, have terrible morale, and live like total pigs in the trenches. That said, the Ukrainian miliary leadership (and I) knew that the current counteroffensive would be nothing like last year's, when the Russian lines quickly broke and we were able to make rapid advances.

In the first days of the current counteroffensive, Ukraine tried a rapid advance using Western equipment, but we always knew that this approach was unlikely to succeed – and it didn't.

Ukraine's primary strategy is to put enormous pressure on Russian forces across the entire front line – like a 500,000-pound press on a steel beam – and eventually it will shatter.

There are six points where this might happen – and it's already starting to happen in two – maybe three – places.

The Ukrainians are determined to liberate Mariupol by the end of the year – and I think they'll do so.

Here's a similar assessment by an analyst, Tom Cooper, The right Stuff... erm... Metrics, which I sent to my Ukraine e-mail list yesterday (to sign up for it, simply send a blank e-mail to: ukraine-subscribe@mailer.kasecapital.com).

I agree with Nance and Cooper.

My contacts on the ground report that Russian forces are weakening, so Ukraine is ramping up its counteroffensive. I expect this will result in significantly more rapid territorial gains in the next couple of months than what we've seen so far...

Best regards,

Whitney

P.S. I welcome your feedback at WTDfeedback@empirefinancialresearch.com.