Regional Bank Stocks Close at Lowest Level Since 2020; Half of America's banks are potentially insolvent; Yesterday may have marked a bottom; Lessons from Wells Fargo during the global financial crisis

1) Regional bank stocks took a beating yesterday: Regional Bank Stocks Close at Lowest Level Since 2020. Excerpt:

Shares of a number of midsize lenders fell sharply Tuesday following the collapse of First Republic Bank, a sign that investors are still worried about the industry's health in a world of higher interest rates.

Banks that took a hit following the March collapse of Silicon Valley Bank fell the most. Los Angeles-based PacWest dropped 28%, while Phoenix-based Western Alliance fell 15%. Metropolitan Bank, based in New York, declined 20%.

A broader index of regional-bank stocks fell more than 5% to its lowest close since 2020. Citizens, Truist, and U.S. Bank each shed about 7%. The biggest banks also fell but the declines were less severe. Bank of America and Wells Fargo slid a respective 3% and 4%, while JPMorgan was down nearly 2%.

2) For further insight into the reasons behind the sell-off, see this opinion piece from the U.K.'s Telegraph (subscription required, but you can bypass it by using Pocket, about which I wrote here): Half of America's banks are potentially insolvent – this is how a credit crunch begins. Excerpt:

The twin crashes in U.S. commercial real estate and the U.S. bond market have collided with $9 trillion uninsured deposits in the American banking system. Such deposits can vanish in an afternoon in the cyber age.

The second and third biggest bank failures in U.S. history have followed in quick succession. The U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve would like us to believe that they are "idiosyncratic". That is a dangerous evasion.

Almost half of America's 4,800 banks are already burning through their capital buffers. They may not have to mark all losses to market under U.S. accounting rules but that does not make them solvent. Somebody will take those losses.

"It's spooky. Thousands of banks are underwater," said Professor Amit Seru, a banking expert at Stanford University. "Let's not pretend that this is just about Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic. A lot of the U.S. banking system is potentially insolvent."

The full shock of monetary tightening by the Fed has yet to hit. A great edifice of debt faces a refinancing cliff-edge over the next six quarters. Only then will we learn whether the US financial system can safely deflate the excess leverage induced by extreme monetary stimulus during the pandemic.

A Hoover Institution report by Prof. Seru and a group of banking experts calculates that more than 2,315 U.S. banks are currently sitting on assets worth less than their liabilities. The market value of their loan portfolios is $2 trillion lower than the stated book value.

These lenders include big beasts. One of the 10 most vulnerable banks is a globally systemic entity with assets of over $1 trillion. Three others are large banks. "It is not just a problem for banks under $250 billion that didn't have to pass stress tests," he said...

predicts that the banking crisis will keep moving up the food chain from the original outliers to mainstream banks until the Fed backs off and slashes rates by 100 basis points.

The Fed has no intention of backing off. It plans to raise rates further. It continues to shrink the US money supply at a record pace with $95 billion of quantitative tightening each month.

The horrible truth is that the world's superpower central bank has made such a mess of affairs that it has to pick between two poisons: either it capitulates on inflation; or it lets a banking crisis reach systemic proportions. It has chosen a banking crisis.

3) I think these fears are way overblown and that yesterday's sell-off – and this hysterical, over-the-top, wrongheaded article – may mark a bottom for the sector, for two main reasons...

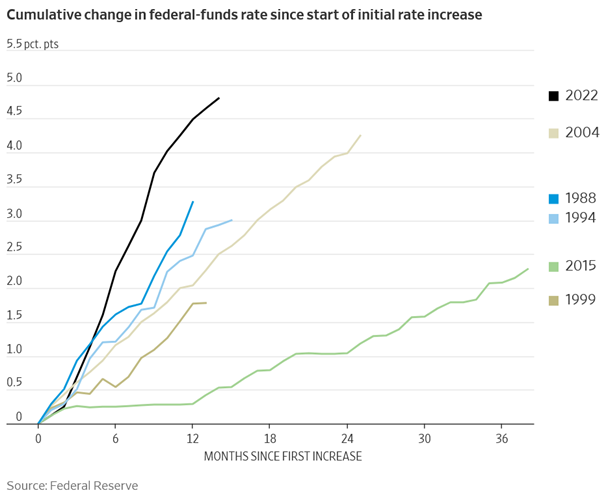

First, this "crisis" was caused by the Fed's unprecedented sharp increases in interest rates, which you can see in this chart from the Wall Street Journal:

But here's the thing: if the banking sector truly does enter a crisis, the Fed can quickly cease or reverse its rate hikes, eliminating the bondholders' losses (here's a good article in the Wall Street Journal trying to read the tea leaves on this: What a Fed Debate 17 Years Ago Reveals About Its Rate Deliberations Now).

This is a fundamental difference between today's situation versus the global financial crisis, when banks had actual losses in their loan portfolios.

4) "Ah, but what about the losses banks are likely to incur in the coming years in their commercial loan portfolios?"

Banks will indeed take substantial losses... but investors are forgetting that these losses won't be sudden, but rather spread out over time – which means that banks can offset losses with profits.

This is a topic I discussed at length in the Wells Fargo (WFC) chapter of my 2009 book about the financial crisis, More Mortgage Meltdown: 6 Ways to Profit in These Bad Times. Here are excerpts from the conclusion of that chapter:

We estimate that Wells Fargo will incur $52 billion to $124 billion of losses on its $865 billion loan book, or 6% to 14%. Even the low end is more than double Wells Fargo's $21.7 billion provision for credit losses, so in light of the company having little or no real equity, does this mean we think Wells Fargo is likely to meet the same fate as Citigroup? Not necessarily. Allow us to explain.

Wells Fargo is currently in a race for its life. Its losses are digging a hole every quarter, which will continue for the foreseeable future, so Wells Fargo's challenge is to earn profits fast enough to fill the hole before it engulfs the company. We think it's likely to do so, which is why we now own the stock. It's going to be a close call, however, which is why it's not a very big position – there's still a real possibility of a bad outcome.

Everything hinges on how quickly the losses come in and how much money Wells can earn. The $21.7 billion provision for credit losses provides a bit of a cushion, which Wells Fargo said during its January 28, 2009 conference call "covers 12 months of estimated losses for consumer loans and at least 24 months for commercial loans."

We think that's optimistic, but it still underscores the good news for the company that its loans will take time to default. Unlike toxic securitized finance products like RMBSs and CDOs, which have to be marked down very quickly, actual loans take time to season and companies have some leeway as to when they take charge-offs and recognize losses.

For example, Wells Fargo is aggressively working with many at-risk homeowners and businesses to modify loans and reduce the chances of default. In a race against time, it's critically important that Wells Fargo have these tools at its disposal.

Another plus is that Wells Fargo's management finally seems to have awakened to how perilous the situation really is, which led it to slash the dividend and even more aggressively cut costs.

As we showed at the beginning of this chapter, Wells Fargo is generating pretax, pre-provision earnings of approximately $30 billion to $34 billion annually ($7.5 billion to $8.5 billion per quarter) even before $5 billion in cost cuts and synergies kick in, which will likely boost this to $10 billion per quarter.

When combined with the $21.7 billion provision for credit losses, are these profits enough for Wells Fargo to keep ahead of the $52 billion to $124 billion of losses to come? We think it's likely...

The combined company's quarterly provision for credit losses would be $8 billion in early 2009, rising to $10 billion by the end of the year.

As high as this is, it is almost precisely matched by the $8 billion to $10 billion of quarterly pretax, pre-provision profits we expect Wells Fargo to earn, so it current $21.7 billion cushion would see little impairment and the company would likely make it through the storm. As noted earlier, however, if some combination of weaker profits and higher losses occurs, Wells Fargo might end up a ward of the government, like Citigroup.

In summary, we think if Wells Fargo makes it through the storm without significant dilution of its shareholders, perhaps a 70% likelihood in our estimation, it will earn $4 to $5 per share, which would translate into a $40 to $60 stock. That kind of upside offsets the very real downside risk and makes the risk-reward equation highly favorable when the stock is in the $10 to $15 range, which is why we now own it.

Sure enough, WFC shares rose roughly 400% to nearly $60 in the next five years...

Best regards,

Whitney

P.S. I welcome your feedback at WTDfeedback@empirefinancialresearch.com.