What a day!; Why I'm trembling with greed; Two critical developments; When I think stocks are likely to bottom; When do you think they will?; Are you an investor or a speculator?

1) Wow... I haven't seen a day like yesterday in the markets – with such extreme levels of fear, dislocation, and capitulation – since the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. It was the U.S. market's biggest single-day decline in 33 years and the MSCI World Index's largest fall ever. The CBOE Volatility Index ("VIX") fear gauge closed within a hair of its all-time high in late 2008.

The S&P 500 Index closed down 23.2% year to date and 26.7% from its all-time high on February 19. Though other market declines have been far greater – the worst being the 86.2% collapse in the Dow Jones Industrial Average from September 16, 1929 to June 1, 1932 – it's the fastest entry into a bear market ever – truly a 100-year storm.

There have been some ugly days during this "flash bear market" in the past three weeks, but this one felt much worse...

2) As a human and as an American, I'm gravely concerned about the coronavirus pandemic. I underestimated its severity, especially the societal impact – mea culpa.

But I remain convinced that the investor panic is overdone.

As an investor, I couldn't be happier – my feelings are captured by a wonderful phrase I learned decades ago from my friend and former hedge fund manager, Chris Stavrou: "I'm trembling with greed!"

There are many reasons to be optimistic: our economy is enormous and was doing quite well on the eve of this crisis. American households have the least leverage since 1984 (measured by total liabilities divided by total assets). The U.S. government, if need be, can easily borrow trillions of dollars at minimal rates. Similarly, the Federal Reserve has ample room for more quantitative easing. And don't forget that President Donald Trump views a recovery in stock prices as critical to his re-election hopes.

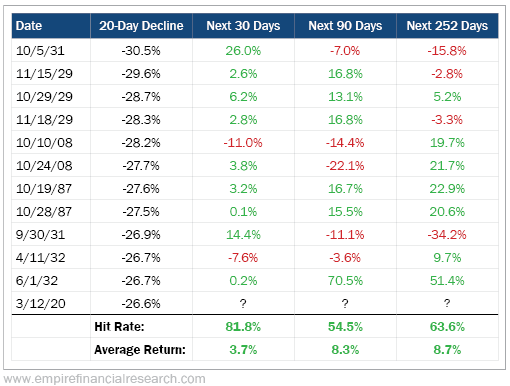

Stock market history provides some comfort as well. In the past 94 years, the S&P 500 has only fallen more than 20% six times (1930, 1931, 1937, 1974, 2002, and 2008). And the 11 prior times that the S&P 500 fell as much as it has in the past 20 days (all during the Great Depression, the 1987 Black Monday crash, and the Great Financial Crisis), over the next 30, 90, and 252 trading days later (the latter is one calendar year), it has been higher nine, six, and seven times, respectively, as this chart shows:

Most important, I want to highlight two critical developments this week that, I believe, have set us up for large profits, possibly very quickly...

The first is obvious: Stocks are cheaper – many are a lot cheaper – than they were only a short while ago. The decline in the major indexes is bad enough, but these primarily reflect the performance of large-cap, blue-chip stocks, which is masking absolute carnage across thousands of smaller stocks. Most of the stocks I follow are down at least 40% to 50%, sometimes more. While these sharp declines have been painful, many of these stocks are now incredibly cheap in my opinion.

The second reason I'm bullish is that we, the American people, and our leaders finally seem to be taking this pandemic seriously and are taking (or will likely soon take) many of the steps that I outlined in yesterday's e-mail. As a result, I'm cautiously optimistic that we will contain the spread of the coronavirus – without completely shutting down the country, as China and Italy did.

3) So when will stocks bottom? I'm not sure, but I'd guess roughly when the news flow about the coronavirus crisis starts to get less bad.

Note that I didn't say "starts to get better." It's important to understand this distinction because investors are always forward-looking, so stocks tend to move in anticipation of a turn.

For example, during the Great Financial Crisis, the market bottomed in March 2009 not when the economic indicators turned positive, but when their rate of decline started to slow – a second-derivative effect.

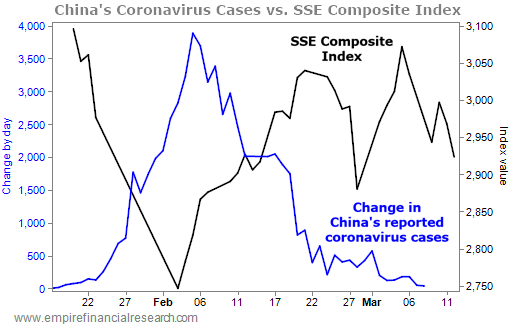

In the case of the current crisis, I think stocks will bottom when the daily count of new confirmed coronavirus cases starts to slow, both in the U.S. and worldwide (excluding China).

This isn't just a theory I concocted – it's based on what actually happened in China, where the virus originated. Take a look at this chart I put together, which shows that the main Chinese stock index, the Shanghai Composite, bottomed on almost the exact day that the number of new coronavirus cases stopped going up:

This didn't take long. Though the epidemic had been growing for months, the number of new cases each day in China rose sharply for a mere 19 days before China's unprecedented actions took effect. The government locked down not just the city of Wuhan – the epicenter of the virus – but the entire Hubei Province of 60 million people... And it imposed severe restrictions across large swaths of the rest of the country.

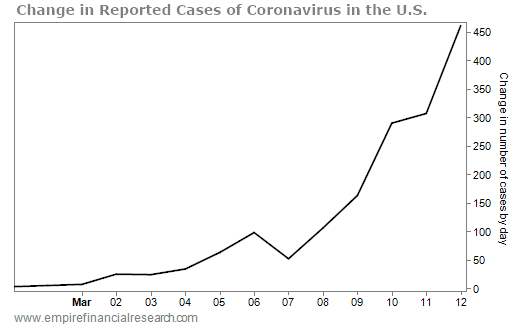

Given that few other countries have the ability or appetite to impose such strong measures, it will likely take them longer to halt daily growth in new cases. How much longer? Who knows...

If it takes 30 days, that would mean we have another roughly two weeks of rising cases – and, likely, tumultuous stock markets – in both the U.S. and the rest of the world (excluding China), as you can see in these two charts:

(You can track this data for yourself, in real time, on this website.)

If I'm right about this, am I saying that stocks are likely to keep falling for at least another two weeks? Not necessarily, because I think investors are anticipating – and therefore have priced into stocks – a rising number of new coronavirus cases. But it will probably keep markets highly volatile – and I don't expect a breakout to the upside until the number of new cases starts to fall...

4) In yesterday's e-mail, when the S&P 500 was at 2,500, I wrote: "I would guess that... we're within 5% to 10% of the ultimate bottom."

I'd be very curious to hear your best guess about where the index will bottom, as well as when it will recover its losses and hit a new high (meaning it rises 36.4% from yesterday's close). I believe in the "wisdom of crowds" (to quote the title of the excellent book by James Surowiecki), so I would be grateful if you'd take 10 seconds to fill out this two-question survey I posted here. I will share the results next week.

5) As this emotional and exhausting week comes to an end and we all have the chance to reflect over the weekend, I'd like to leave you with some final thoughts.

This is one of those once-a-decade, gut-check moments when everyone needs to look in the mirror and honestly answer the question: "Am I an investor or a speculator?"

During the past 11 years – the longest bull market in history, which just came to a sudden end – there were two overriding lessons: a) buy every dip... and b) the more risk you take, the higher your returns. This spawned millions of bull-market geniuses who thought they were investors but were, in reality, just rank speculators.

I know the type well because I used to be one of them. When I first started investing in the late 1990s, during the last stages of an earlier long bull market, I was buying crazy stocks based on little more than tips from friends. After losing my shirt, I migrated to the most popular growth stocks. I thought I was being smart and conservative, but now realize that they were significantly overvalued when I bought them. Nevertheless, I was rewarded for a few years as an enormous bubble built up – especially in the tech and Internet sector (the Nasdaq Composite Index rose 86% in 1999).

The bubble continued inflating until March 2000, when it turned. The Nasdaq ended up falling a sickening 78% and bottoming in October 2002.

I was fortunate to avoid this carnage because in the years after I launched my first hedge fund in January 1999, I read the right books, made the right friends, and cultivated the right mentors. While it took a while for their collective wisdom to seep into my thick skull, I eventually came to realize that I hadn't really been behaving like a real investor -- though I certainly fancied myself one! Rather, I had mostly been speculating in the most popular stocks, without really understanding them or paying any attention to their extreme valuations.

Once I came to this realization, I dumped my speculative stocks (in the nick of time!), started doing in-depth research, and focused on the two underlying principles of all sensible investing – intrinsic value and margin of safety (discussed in chapters 8 and 20 of the bible of value investing, Benjamin Graham's The Intelligent Investor). I've never looked back...

If this description of my early days as an investor is hitting close to home – perhaps because you’ve suffered hideous losses in the past three weeks – then take heart… If a guy like me, with his big ego and fancy Harvard degrees can see the error of his ways and change… so can you!

Best regards,

Whitney