How Hard Should the Fed Squeeze to Reach 2% Inflation?; If the inflation target is wrong, why can't we just change it?; Despite What Powell Says, the Fed Is Likely Done; Chamath Palihapitiya and Vivek Ramaswamy; I climbed Mount Shuksan via the Fisher Chimneys yesterday

1) Continuing the discussion in yesterday's e-mail of the economy, inflation, and what the Fed should/will do, this Wall Street Journal article asks a good question: How Hard Should the Fed Squeeze to Reach 2% Inflation? Excerpt:

Much of the work lowering inflation is done: Amid the most aggressive series of interest rate increases in four decades, it has fallen to 3.2% from 9.1%.

This good news presents the Federal Reserve with a new thorny question. How aggressive should it be in squeezing out what's left?

Their decision holds major implications for consumers, the markets, and the economy – and whether Fed Chair Jerome Powell achieves a so-called soft landing that beats inflation without causing a recession.

Officially, the Fed's target for inflation is 2%. With inflation running well above that number, officials are still focused on whether to raise rates one more time this year. But that is a relatively small consideration compared with the bigger question of how long to keep rates at that high level.

Fed officials could try to get to 2% quickly, such as by the end of next year, by raising rates higher and only slowly reducing them as the economy weakens. That would risk a sharper downturn and possibly kill the chances of achieving the soft landing.

On the other hand, if they're satisfied that inflation is slowing durably, they could hold them at their current level and consider trimming rates later next year. That would take more time to get to the inflation target – around three years.

What if getting to 2% isn't worth the pain? Another strain of thinking says the Fed should accept a rate around 3% as the new target. Powell and other Fed officials say moving the goal posts like that isn't an option.

New York Times columnist Paul Krugman argues that the Fed should change its target, though he thinks it'll be unofficial: None Dare Call It Victory Excerpt:

So if the 2% target was probably a mistake, and if we could do it over again, we'd probably go for 3%, why not just declare victory over inflation today?

OK, I've been in meetings with current and former central bankers, and the reaction you get if you suggest accepting current inflation and revising the target accordingly is more or less the reaction I imagine you'd get if you waved a Pride flag at a DeSantis rally (although you're less likely to get beaten up or shot). Why?

The main answer seems to be concerns that accepting somewhat higher inflation – even if the economics suggest that the conventional target is too low – would damage central banks' credibility. That's not an entirely foolish concern, although monetary credibility probably matters much less for real-world inflation than central bankers tend to imagine.

On the other hand, should policy be permanently locked into a target that now looks wrong out of fear that changing it will make policymakers look weak?

At this point I see three ways this could go:

- The Fed could adopt the position attributed (dubiously) to John Maynard Keynes – "When the facts change, I change my mind" – and openly adopt a new inflation target.

- The Fed could adopt a policy of strategic hypocrisy, insisting that its target hasn't changed while in practice allowing inflation close to 3% for several years; then, once it has become clear that such a policy won't allow runaway inflation, finally change the formal target.

- The Fed could put its money (supply) where its mouth is and do whatever it takes to get inflation all the way back down to 2%, even if this involves a recession.

As far as I can tell, Option 1 just isn't on the table. Option 2 looks like the most likely strategy. But it's possible that the Fed will feel obliged to prove its toughness by getting back to 2%, even though that's probably bad economics.

If the Fed does seem to be going that route, however, policymakers should be challenged: Should American workers really be asked to lose their jobs for someone else's mistake?

I agree with Krugman that Option 2 is most likely, which is why I agree with this WSJ article: Despite What Powell Says, the Fed Is Likely Done. Excerpt:

There were some hawkish-sounding aspects to what Powell said, including a pledge to raise rates further if necessary, and that appeared to spook investors at first, with stocks falling in early trading. But the substance of what Powell said indicated that if another hike comes, it probably won't occur when policy makers meet next month. And his assessment that the central bank is now "in a position to proceed carefully," suggests the Fed isn't in a rush to do much of anything. Stocks ended the day higher.

One reason Powell put the situation the way he did is that even if policy makers suspect they won't need to raise rates again – especially in consideration of how the full effects of hikes already made have yet to hit the economy – they don't want to take away the option to raise rates further if inflation heads off in the wrong direction again.

Another is that as soon as the Fed says it probably won't raise rates again, investors' focus will quickly shift to when the Fed might start cutting. If they do that, long-term interest rates in particular might start sliding, providing a fresh boost to the economy that policy makers aren't quite ready for. The more time the Fed leaves open the possibility of raising rates, without actually raising them, the less likely it is that investors will start envisioning a rapid series of rate cuts.

And yet the Fed's next move might, in fact, be to cut rates. Its current target on overnight rates, at a range of 5.25% to 5.5%, is the highest in over two decades. And even if one allows for the possibility that the just-right level of rates for when the economy is in balance might now be higher than it was before the pandemic, it is probably still significantly lower than the Fed's target is right now. Or, as Powell put it, "We see the current stance of policy as restrictive, putting downward pressure on economic activity, hiring, and inflation."

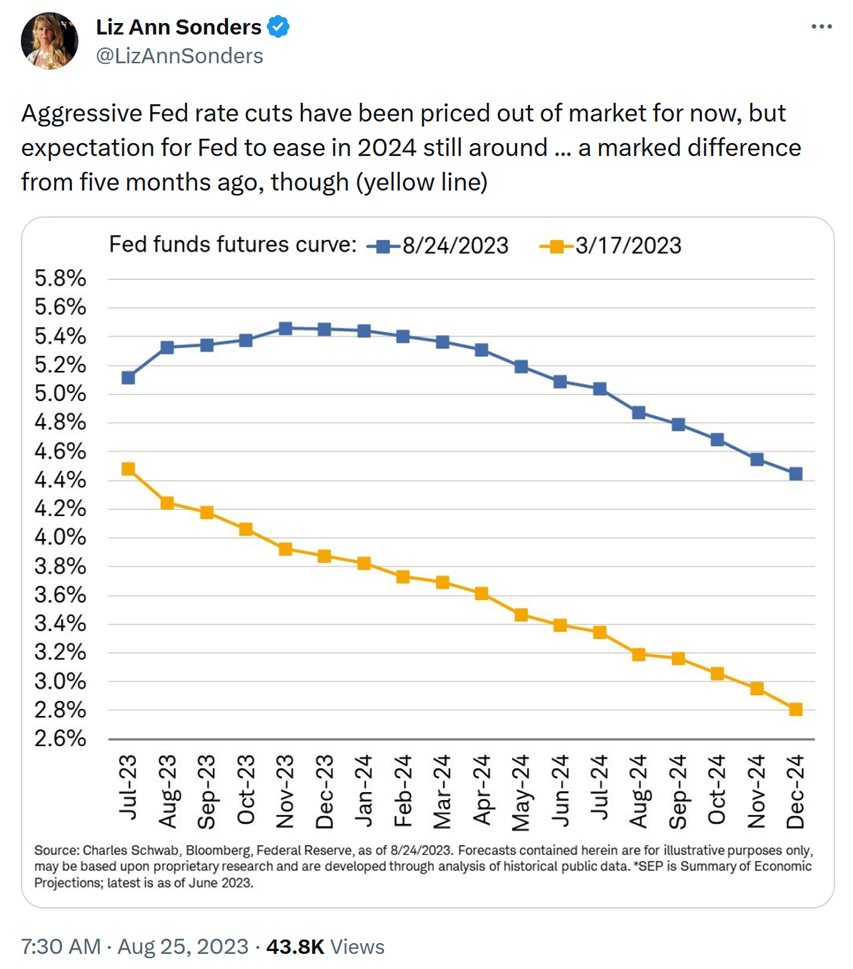

Adding everything up, here is what the market thinks the Fed will do in the next 16 months:

My view is somewhere in between: I think inflation is well under control and will remain in the 3% to 4% range, which likely means the Fed is finished raising rates – and will eventually (late this year or early next year) even feel comfortable lowering them a bit.

2) I've been warning my readers about self-proclaimed "next Warren Buffett" Chamath Palihapitiya since February 24 last year, when I wrote:

My observation over the past two decades is that anytime a "new economy" guru compares himself to – while also trash talking – the Oracle of Omaha, the market soon punishes his hubris! The King of SPACs Wants You to Know He's the Next Warren Buffett.

This New York Times article in December exposes him as the con man that he is: The 'SPAC King' Is Over It.

On January 17, I wrote:

Palihapitiya reminds me of ARK Invest's Cathie Wood, whose main fund, the ARK Innovation Fund (ARKK), recently hit a five-and-a-half-year low a few weeks ago.

However, Palihapitiya is worse in my book because I think he knows he's lying when he pumps worthless stocks, whereas Wood actually appears to believe the nonsense that she's spewing, such as her recent prediction that bitcoin is going to $1 million.

He's also worse because he appears to feel no remorse, this recent Slate article notes: The SPAC King Grants an Audience to His Former Subjects. Excerpt:

In any just world, Chamath Palihapitiya would be ashamed of himself.

The well-known venture capitalist and podcaster lent his reputation to a slew of companies going public via his special-purpose acquisition companies. He was the ruinous "SPAC King."

Now, almost a year after calling it quits on two SPACs, he's still in denial that he was the Pied Piper who enticed retail investors into betting on speculative, money-losing companies. He's like a bully who stole someone's lunch money and then says, "Stop crying about it" – except it's for all the world to see.

This week on X, Palihapitiya is dunking on people who say that they lost money because of him.

He has said he made roughly $750 million by throwing his reputation behind the stocks, taking them public via SPACs that he helmed, then selling shares on the public markets. He hyped the stocks, he sold his shares, and he made a profit while the retail investors who trusted him lost money.

And the reality is that Palihapitiya got away with it. He's boastfully summering in Italy and reveling in his luxurious wedding on All-In, the podcast that he co-hosts. Elon Musk and Grimes were apparently in attendance.

3) Rapidly rising presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy reminds me a lot of Palihapitiya – not because they're both of descent from the Indian subcontinent, but because they're smooth-talking salesmen with histories of costing investors billions.

(Note that I try my best to keep politics out of these e-mails, so I am only commenting here on Ramaswamy's business history.)

Ramaswamy made his roughly billion-dollar fortune by founding a biotech company, Roivant Sciences (ROIV), which went public two years ago by merging with a SPAC. Despite having minimal revenue ($79 million in the last year), the stock is up from its $10-per-share IPO price. After tumbling to under $3 per share last September, it has rallied strongly to around $11 per share – giving the company a market cap of $8.7 billion, despite staggering losses of around $1 billion over the past year.

With only $1 billion in net cash and no sign that its cash burn is diminishing, Roivant could soon be in trouble.

That said, many successful drug development companies have similar financials in their early days, which rapidly improve when they launch an innovative new drug – or they get snapped up at a big premium by one of the industry giants.

So, is Roivant on the verge of something similar? I don't know, as I don't have the expertise to evaluate the company's drug pipeline.

But based on what happened with its first drug, count me skeptical. According to this Financial Times article, From biotech booster to Republican contender: the rise of Vivek Ramaswamy, and this YouTube video by entrepreneur Kevin Paffrath, Exposing a Multibillion Dollar FRAUD, this is what happened (from the FT article):

Ramaswamy earned part of his fortune by touting the promise of an experimental Alzheimer's medicine he acquired from GSK for just $5mn in 2015. In private, executives at the British pharma company were scathing about the drug's prospects, arguing they would not have parted with the molecule for such a small sum if it had any chance of success.

He purchased the medicine via Roivant, his drug development group, before creating a subsidiary named Axovant to develop it. Axovant filed for an initial public offering that raised $315mn in the largest biotech flotation on record, securing a valuation of $3bn after the first day of trading.

Then aged just 30, Ramaswamy promised to unearth other forgotten compounds and turn Roivant into what he described as the "Berkshire Hathaway of drug development". In doing so, he would generate "the highest return on investment endeavor ever taken up in the pharmaceutical industry."

The valuation of Roivant, then a privately-held company, increased after the IPO and Ramaswamy in 2015 sold part of his stake to Viking Global Investors. His tax return for that year shows $37mn in capital gains.

However, as GSK had privately predicted, the medicine was a flop and in 2017 it failed clinical trials, causing Axovant's shares to collapse. Roivant's holding company structure insulated it from the worst of the crash but other investors lost millions of dollars. Earlier this year, shareholders of Axovant, since renamed SioGene, voted to liquidate and dissolve the company.

The Paffrath video is even more damning...

So was this a good-faith effort to develop a major new drug to treat a horrific disease, or a total scam?

Again, it's hard to know... but I think the Ramaswamy campaign's response to Paffrath is telling. As he recounts in a follow-up video, Vivek Ramaswamy *JUST* Responded to Me , rather than address any of the issues Paffrath raised, the campaign simply engaged in ad hominem attacks.

It's clear that investors would be well served to avoid ROIV like the plague...

4) My guide Paul and I summited Mount Shuksan via the Fisher Chimneys yesterday – a 14-hour round-trip from Lake Ann. It was an epic day as you can see from these pictures:

This is my eighth annual climb to raise money for my favorite charity, KIPP charter schools, to help thousands of KIPPsters on their even bigger climbs to and through college.

If you'd like to support my climbs for KIPP, you can do so here.

Thank you!

Whitney

P.S. I welcome your feedback at WTDfeedback@empirefinancialresearch.com.