Berkshire Hathaway after Buffett; No Buffett premium in the stock; Berkshire's culture; The biggest risk shareholders should worry about; Apple after Steve Jobs; Squishmallows

1) In response to yesterday's e-mail about Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B) and its valuation, my editor in chief asked the question people have been asking for decades, but is now more relevant given that Buffett is 92: What will happen to Berkshire when he's gone, and how does that affect my calculation of its intrinsic value?

The short answers are to both are: not much.

When Buffett steps aside, which I'd guess is at least five years off (look at Munger, still going strong at 99!), his job will be split into two parts: Greg Abel as CEO (with Ajit Jain continuing to run Berkshire's insurance operations) and two Chief Investment Officers, Todd Combs and Ted Weschler.

I have met and studied all four of these men closely and think they're superb, so Berkshire shouldn't miss a beat.

That said, no one will be able to fully fill the shoes of the greatest investor of all time and Berkshire will be slightly diminished when Buffett is no longer running it for a number of reasons.

First, no one has Buffett's experience, wisdom, and track record, so his successors' decisions regarding the purchases of both stocks and entire businesses might not be as good.

Second, most of the 80-plus managers of Berkshire's operating subsidiaries are wealthy and don't need to work, but nevertheless work extremely hard and almost never leave thanks to Buffett's "halo" and superb managerial skills.

Will this remain the case under his successors? It wouldn't surprise me if a handful of these managers – many of whom, like Buffett and Munger, are well past normal retirement age –choose to step down after Buffett does.

Third, Buffett's relationships and reputation are unrivaled so he is sometimes offered deals and terms that are not offered to any other investor – and might not be offered to his successors.

Lastly, being offered investment opportunities (especially on terms and/or prices not available to anyone else) also applies to buying companies outright. There's a high degree of prestige in selling one's business to Buffett (above and beyond the advantages of selling to Berkshire). For example, the owners of metal cutting toolmaker Iscar could surely have gotten a higher price had they taken the business public or sold it to an LBO firm.

But these are relatively minor factors and/or low-probability events.

2) I'd worry about owning Berkshire's stock after Buffett if there were a "Buffett premium" built into it, but there's not.

To arrive at my estimate of intrinsic value, which I calculated in yesterday's e-mail, I simply took cash and investments per share and added the value of the operating businesses, based on a conservative multiple of their normalized earnings, to arrive at $567,000 per A share or $378 per B share, 14% above today's price.

When Buffett steps aside, the value of the cash, stocks, and bonds won't change, nor will the value of all the operating businesses like Burlington Northern railroad, insurer GEICO, etc.

3) Another risk-mitigating factor is that Buffett has built a powerful culture that is likely to endure.

Berkshire operates via extreme decentralization. Though it is one of the largest businesses in the world with nearly 400,000 employees, only 26 are at Berkshire's headquarters in Omaha. There is no general counsel or human resources department.

Here's what Munger had to say about Berkshire's culture back in 2007...

By the standards of the rest of the world, we over-trust. So far it has worked very well for us. Some would see it as weakness.

A lot of people think if you just had more process and more compliance – checks and double-checks and so forth – you could create a better result in the world. Well, Berkshire has had practically no process. We had hardly any internal auditing until they forced it on us.

We just try to operate in a seamless web of deserved trust and be careful whom we trust.

In 2014, a New York Times article noted...

Behavioral scientists and psychologists have long contended that "trust" is, to some degree, one of the most powerful forces within organizations. Mr. Munger and Mr. Buffett argue that with the right basic controls, finding trustworthy managers and giving them an enormous amount of leeway creates more value than if they are forced to constantly look over their shoulders at human resources departments and lawyers monitoring their every move.

4) I think the biggest risk Berkshire's shareholders should think about is if Buffett begins to lose it mentally and starts making bad investment decisions, but he doesn't recognize it (or refuses to acknowledge it because he loves his work so much) and the board won't remove him, perhaps rationalizing that a diminished Buffett is still better than anyone else.

Buffett is aware of this risk and has instructed Berkshire's board members, both publicly and privately, that their most important job is to "take away the keys" if they see him losing it.

I trust that both Buffett and the board will act rationally, but I also view it as my job to independently observe and evaluate Buffett to make sure I'm comfortable that he's still at the top of his game. Today, I think he's never been better!

5) In summary, the most comparable example of a business that, like Berkshire, is closely associated with its legendary founder and CEO is Apple (AAPL).

As Steve Jobs' health began to fail, he assumed fewer day-to-day responsibilities, passing them to top lieutenants. He resigned as CEO on August 24, 2011, and died exactly six weeks later on October 5, 2011.

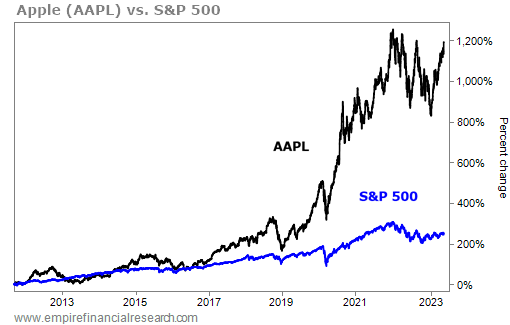

Apple's stock declined less than 1% on the first trading days after both his retirement and death, and is up 1,200% since then, five times more than the S&P 500, as this chart shows:

6) Berkshire's annual meeting takes place in the main arena of the CHI Health Center – it looks like this:

While the meeting is going on in the main arena, dozens of Berkshire Hathaway subsidiaries are hawking their wares in a massive nearby room – here are some pictures I took:

A new company had a booth this year, Jazwares, a subsidiary of Alleghany, which Berkshire acquired last year. Jazwares owns Squishmallows, a brand of adorable stuffed toys that market research firm NPD Group named America's best-selling toy last year. Here's a picture of its booth:

Jazwares cleverly created Squishmallows of Buffett and Munger – small ones 8 inches tall for $10 and large ones 16 inches tall for $20 – which were only available on site and were selling like hotcakes. The current bid for a pair is $255 on eBay!

I bought three each of the big ones – two for me and two each for my buddies Glenn Tongue and Chris Stavrou. I think they make a wonderful addition to my living room:

And Rosie (the Wonder Dog) and Phoebe (the Wonder Pup) love them:

Best regards,

Whitney

P.S. I welcome your feedback at WTDfeedback@empirefinancialresearch.com.