Berkshire Hathaway is below Buffett's buy price; Boeing's Fatal Flaw; The Airline Safety Revolution; Phoebe's first train ride

1) A hat tip to my friend and former colleague Glenn Tongue, who's the ax on Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B), for flagging this for me. He writes:

Berkshire Hathaway Chairman and CEO Warren Buffett is without doubt a first-ballot hall of famer when it comes to investing. He is known for intelligent and rational capital allocation, and when Berkshire discloses a new position, the acquired stock inevitably jumps.

So what has Buffett been purchasing recently? We won't for sure until the company reports third-quarter earnings in early November, but I think we're likely to see large purchases of his own stock.

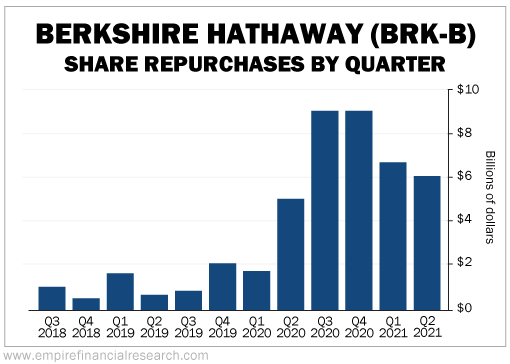

This chart shows the massive increase in repurchases over the last five quarters:

This table in Berkshire's second-quarter 10-Q filing shows the prices at which Buffett was repurchasing his own shares:

We can see that $432,000 per A-share (or $288 per B-share) was Buffett's repurchase sweet spot – yet the stock closed yesterday nearly 5% below this at only $412,081.

One of the world's greatest investors thinks his stock is a bargain at $432,000 – yet I can buy it for $20,000 per share less. That sounds pretty good to me! Historically, buying Buffett's best ideas below his purchase price has almost always turned out well...

Thank you, Glenn!

I'd add that in my August 9 e-mail, I showed the calculations behind my estimate that Berkshire's intrinsic value is $513,000 per A-share, which means the stock today is an 80-cent dollar. I can't think of any stock offering this combination of safety and growth trading anywhere near this level of discount.

That said, keep expectations modest. Berkshire long ago became so large that it transitioned from a "get rich" stock to a "stay rich" stock. Thus, even at this price, I'd expect it to outperform the S&P 500 Index by perhaps five percentage points annually for the next five years.

2) This new Frontline documentary, Boeing's Fatal Flaw, is an excellent piece of investigative journalism. Here's a summary:

In October 2018, a Boeing (BA) 737 Max passenger jet crashed shortly after takeoff off the coast of Indonesia. Five months later, following an eerily similar flight pattern, another 737 Max 8 went down in Ethiopia. Everyone on board the flights died.

Boeing's Fatal Flaw, a Frontline documentary in collaboration with the New York Times, tells the inside story of what led up to the crashes – revealing how intense market pressure and failed oversight contributed to tragic deaths and a catastrophic crisis for one of the world's most iconic industrial names.

3) Despite these two crashes, however, air travel has become much safer, especially in the U.S. This insightful Wall Street Journal article documents how this happened: The Airline Safety Revolution. Excerpt:

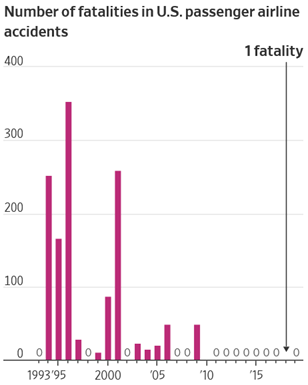

Over the past 12 years, U.S. airlines have accomplished an astonishing feat: carrying more than eight billion passengers without a fatal crash.

Such numbers were once unimaginable, even among the most optimistic safety experts. But now, pilots for domestic carriers can expect to go through an entire career without experiencing a single engine malfunction or failure. Official statistics show that in recent years, the riskiest part of any airline trip in the U.S. is when aircraft wheels are on the ground, on runways, or taxiways.

The achievements stem from a sweeping safety reassessment – a virtual revolution in thinking – sparked by a small band of senior federal regulators, top industry executives and pilots-union leaders after a series of high-profile fatal crashes in the mid-1990s. To combat common industry hazards, they teamed up to launch voluntary incident reporting programs with carriers sharing data and no punishment for airlines or aviators when mistakes were uncovered.

The pioneers bucked deep-seated doubts from some insiders and outright opposition from pilots' groups worried about disciplinary blowback. By the end of the 1990s, the Federal Aviation Administration, plane maker Boeing, labor representatives and the largest U.S. airline trade association all endorsed the unified, data-driven safety agenda. Together, they devised steps to make it happen.

Their approach was simple in its fundamentals but wickedly difficult to implement at the start, requiring unprecedented levels of trust among the participants. During the early stages, representatives of pilots and carriers grudgingly agreed to share information with each other, as well as with the government, regarding budding hazards and near-crashes. Tentative cooperation was dependent on FAA pledges that good-faith mistakes and procedural violations wouldn't result in enforcement actions.

The results have been remarkable. In 1996, before the safety reboot began, U.S. carriers had a fatal accident rate of roughly one crash for every two million departures. That year alone, more than 350 people died in domestic airline accidents, including 230 in the infamous fuel-tank explosion on TWA Flight 800 that sucked scores of passengers out of the fractured fuselage. Within 10 years, the fatal accident rate had been reduced by more than 80%, beating a goal set by a White House commission.

Today's travelers are benefiting from another decade-plus of improved safety for U.S. carriers, and the fatality rate has been driven down to one for every 120 million departures. (The single passenger death in the past dozen years was from an engine fan blade coming apart during a 2018 flight.) Yet neither the scope nor the significance of the underlying changes, expanded year after year with little fanfare, is generally recognized by the flying public.

"The magnitude of the improvement has far exceeded my expectations," said Randy Babbitt, head of the FAA from 2009 to 2011, who previously championed many of the early advances as president of North America's largest pilots union. The payoff turned out to be so dramatic overall, he added, "It's almost like buying a lottery ticket for 10 bucks and winning the jackpot."

As I read this, I can't help but wonder why we can't apply similar techniques to improve our health care and educational systems... Well, sadly, here's one answer:

Part of the industry's motivation was self-preservation. A lone jumbo jet crash with mass fatalities, according to industry estimates, can amount to a financial hit of nearly $1 billion, including insurance payouts, additional legal liabilities, lost business and reputational damage.

4) Phoebe (the Wonder Pup) and I took the train to Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire yesterday.

I wanted to see my parents the last few days they're here, go to the Laver Cup tennis tournament in Boston this weekend, and bring home our Subaru on Sunday (which has just been repaired after some bozo backed into it in a parking lot while my youngest daughter was driving it in Maine a couple of months ago, causing nearly $4,000 of damage).

We'd usually take the Dartmouth Coach nonstop bus from New York City to Hanover, New Hampshire, which only takes five hours, but they don't allow dogs. So instead we took the Amtrak ("Vermonter") train, which took seven hours to get to White River Junction, where my parents picked me up. (Amtrak allows dogs in carriers weighing no more than 20 pounds total for an extra $25 charge.)

Phoebe was an absolute champ, lying quietly in her carrier, either sleeping or chewing on her bully stick.

When we stopped for 15 minutes in Springfield, Massachusetts, I took her out and put her pee pad down, but despite my encouragement, she didn't use it – she just wanted to walk around, explore the platform, and get some love from random people...

Here are some pictures...

The picture in the lower right is of Phoebe and Rosie (the Wonder Dog) in the cute doggy "The Girls" frame Susan and I bought in Idaho last week.

And this morning, Phoebe ran around the tennis court while I hit with my new Slinger ball machine. Here's a short video of it.

Best regards,

Whitney

P.S. I welcome your feedback at WTDfeedback@empirefinancialresearch.com.