In This Episode

On this week's Stansberry Investor Hour, Dan and Corey welcome author Alex Epstein to the show. Alex has written several books advocating for the use of fossil fuels, including his most recent work, Fossil Future. The self-described "energy-freedom advocate" joins the podcast to challenge the popular climate-change narrative and provide more context for the crucial role fossil fuels play in society.

Alex kicks things off by weighing in on the debate around climate change and the effects of fossil fuels. He argues that the benefits of using fossil fuels far outweigh the negatives and that, in many cases, energy can be used to overcome any adverse effects. Alex also breaks down the myth of unsustainability, the anti-human bias implicit in environmentalism, and the incorrect belief that more folks die of climate-related catastrophes today than in the past. Citing a specific example of energy's usefulness, Alex notes...

Energy allows you to do anything... So if you think about, "well, fossil fuels increase the incidence of drought" as a negative side effect, they also give you the ability to alleviate drought as a benefit through things like irrigation and crop transport.

Next, Alex discusses his impact with politicians and lawmakers. He explains that 200 major political offices use his content to direct policy and become more informed on energy topics. Alex then shares his opinion on climate change, pointing out that we're currently in a climate renaissance and that the Earth has never been more livable for human beings. He brings up geoengineering as a way to cool the climate, asserts that the negative environmental impacts are severely overblown, and emphasizes the crucial role energy plays in the economy...

If you're concerned about any threat, including climate, what you want to do is maximize your capabilities as a society... The main thing is you want to have as robust an economy as possible so that you can deal with it and you can be wealthy. It's so crazy to think, "We might have a climate problem, so let's get really poor."

Finally, Alex talks about climate-change rhetoric dominating in elections, the harm that tech companies have done by blatantly lying about being 100% renewable, and why humans should take pride in the fact that we're progressing as a species and learning to use the Earth in new ways. He puts the anti-impact perspective into both a philosophical and historical context, noting that primitive religions believed "sinning" against nature had dire consequences.

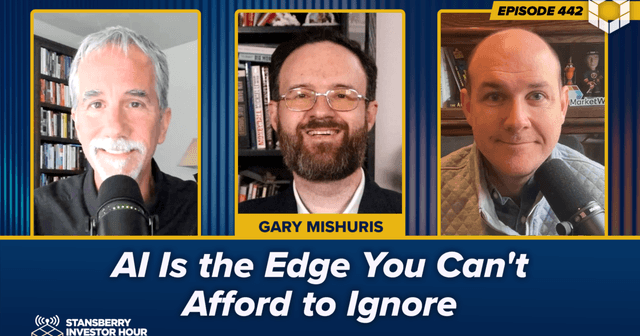

Click here or on the image below to watch the video interview with Alex right now. For the full audio episode, click here.

(Additional past episodes are located here.)

Dan Ferris: Alex, welcome to the show. I'm really glad you could be here with us.

Alex Epstein: Great to be here, guys.

Dan Ferris: All right. I am thrilled to have you here because I've recommended fossil fuel stocks to all my readers. So –

Alex Epstein: Oh, sweet.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So, I like the guy who's championing fossil fuels. And actually, that's where I want to start. I think your perspective is really interesting because a lot of people – for a lot of people this issue is purely a climate thing. They're on one side or another of the climate debate and they say, "Oh, fossil fuels are ruining the atmosphere, etc., etc. They're making everything hotter and worse." And then, on the other side they say, "No, there's no scientific evidence for that. Fossil fuels are fine." But as I – I haven't read every word of your book, Fossil Future, because I don't read every word of anybody's book ever except for great literature usually. But it's awesome to dip into it because just the random dipping in tells me that you are primarily a – you've got a positive attitude about this. You're a fossil fuel advocate – fair to say? – rather than a climate guy.

Alex Epstein: Yeah. Well, yeah, I think it's mainly the context in which you think about climate. So, you're very right that the way this issue is presented as primarily a debate about climate change, which we can find fault with in part because that itself is an extremely vague term. So, to make it a little bit more precise I'd say we have mostly a debate about the climate impacts about fossil fuels. Or maybe a better way to say it we're having a debate about the climate side effects of fossil fuels. So, when we burn fossil fuels it puts more CO2 and other greenhouse gases – but CO2 is the main one we care about – into the atmosphere. And then, what kind of effect does that have on warmth and then other kinds of climate-related phenomena?

And that's a totally valid question. But if you think of it as the climate side effects of fossil fuels, then the other obvious question is, well, what about the benefits of fossil fuels? What about the reasons we're burning fossil fuels in the first place? You can never – with any product or technology you can never out of context just discuss its side effects. And in particular with climate, we even just look at negative side effects. There's very little thought about "Well, could some of these side effects be positive?"

My background is philosophy and this just – once I started learning a little bit about this issue it really struck me we're violating a basic rule of thinking because we're considering a product or technology but we're only considering its negative side effects, whereas what you want to do is you want to consider – you want to carefully weigh benefits and side effects, including positive side effects. And in the case of fossil fuels it's even more of a problem because with most products and technologies the benefits and the side effects are somewhat separate. You take an antibiotic, you get a rash. You can say, "Well, the benefit if more important than the rash" or not. But the – but you still have the rash no matter what. Whereas, one thing with fossil fuels is they can actually cure their own side effects and it's because they're providing energy.

So, energy allows you to do anything because it allows you to use machines, which basically allows you to do anything. So, if you think about, well, if fossil fuels increase the incidence of drought as a negative side effect, they also give you the ability to alleviate drought as a benefit through things like irrigation and crop transport. And if you look at the macro picture over the last hundred years, we're dramatically safer from drought death and all manner of climate-related disaster death.

So, what this points to is we're engaging in the wrong way of thinking in general. And with fossil fuels it makes no sense. And if you start to look at the macro picture, you start to see wait a second, maybe the benefits, including climate-related benefits of fossil fuels, far outweigh the negative side effects, in which case just focusing on negatives and then saying, "If there's negative, let's get rid of fossil fuels," that could be an apocalyptically bad way of thinking, which I think it is.

Dan Ferris: Right. So, this is your – your contrast is – how did you put it in the book? – the human flourishing framework versus –

Alex Epstein: Yeah.

Dan Ferris: – what did you call it? – the anti-impact framework.

Alex Epstein: You got it.

Dan Ferris: And the anti-impact framework being this sort of tendency to focus solely on the negatives. And I notice at one point in the book you also dealt with – everybody who thinks they know something talks about externalities. And it's always – but it's always negative externalities. All the econ students always talk about negative externalities but they don't talk about positive ones. And you do.

Alex Epstein: Well, so let's – let me connect that to this idea of the human flourishing framework because I've sort of addressed one element of that. So, the way I'd put what I've discussed so far is that we're not considering the full context with fossil fuels because we're just looking at negative side effects versus carefully weighing benefits and all side effects, including positive side effects. And then, if you start to drill into it a little bit you can see there's a huge tendency to exaggerate the negative side effects, which makes sense because if you're biased against –

[Crosstalk]

Dan Ferris: Or catastrophize them, actually.

Alex Epstein: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And we'll talk – we can talk about that. So, catastrophized basically means to exaggerate the negatives and then ignore our ability to adapt to or master them, which again makes no sense with fossil fuels because the very – it's not even our ability to adapt to climate challenges from fossil fuels. It's separate from fossil fuels. The same energy that gives us any climate challenges is the core of our ability to adapt to or master those. It's you power the irrigation machines, you power the heating and cooling, you power the infrastructure building, you power the storm warning system.

So, there's this kind of first-level observation if people get the book, which I hope they do. The first chapter is called "Ignoring benefits," and it's pointing out why are you just looking at the negatives? And the second chapter is called "Catastrophizing side effects," so I'm glad you brought that up. Why are you just looking at negative side effects and then exaggerating them and ignoring the offsetting benefits?

And then, there's a question of, well, why are you doing this? And one way to think of it is why do you have a such a bias against fossil fuels? It's kind of like if you see somebody who's super antisemitic or something like this and they just – they can only – they'll see a Jewish person, they can only see negative things about them, and they can't see positives. And you're like "What's going on here? Why can you –" you run into Einstein or something and you can only see negatives about him. But didn't he do some positive stuff?

So, there's always this question of when you run into a bias like that what's the under – what's going on? And one of my arguments is that when you see that kind of bias there's almost always some sort of anti-human assumption and/or anti-human values. In the case of racism, including antisemitism, it's almost always "This group of people isn't really human. They're not a real human. We're a real human. There's something about Jews that just makes them wrong."

And in the case of fossil fuels it's interesting. One of the assumptions, I think, is things that have a lot of impact destroy the Earth. And so, I put it as the delicate nurturer assumption. Nature exists in a delicate nurturing balance. Any significant human impact is going to destroy the balance and us with it. That's just an assumption. And it's a false assumption. It doesn't – it's actually the opposite. So, nature is what I call wild potential. It's dynamic, deficient, dangerous, and we have to impact it a lot to make it livable. That's how we made the Earth a lot more livable, by getting out of the cave. We didn't make it less livable by impacting it a lot.

Dan Ferris: By naturally livable, I believe you said.

Alex Epstein: Yeah, you got it. You're really paying – even if you didn't read all the words, you're paying attention to the right words. So, you've got this one – one thing is we've got this bias against things that have a lot of impact where we think they're going to lead to our destruction. That partially explains the bias against fossil fuels because we see, well, if they're having a lot of impact, even if they haven't ruined the world yet of course they are going to. It's just this dogma that "Well, of course it can't – we can't continue. It can't be "sustainable." The idea of unsustainability comes from this idea of what I call the delicate nurturer.

And then, there's a deeper thing – there's also values. So, why do you – there's something about if somebody is really ignoring the benefits of fossil fuels – and once I start to go into them you see "Wait a second, this is something – there's nothing –" energy is so important to human life. It allows us to become so productive and prosperous by using machines. There's nothing close to fossil fuels for the foreseeable future in terms of providing energy that's affordable, reliable, and available to billions of people in thousands of places.

And then we're in a world where billions of people lack energy to a shocking degree. We have three billion people using less electricity than a typical American refrigerator. You can see – how could you ignore a benefit on that scale? That's not just some secret benefit. If you're in the know – if you're not in the know, then you just don't know. But what I come to is ultimately if you're ignoring a benefit on that scale you're not really concerned with human life. And that's a hard pill to swallow.

But I'll give you an example, which I think is very illustrative. People who say today that we've destroyed the climate, which is a very common thing to say: We've destroyed the climate, the climate is worse than ever.

Dan Ferris: Oh, yeah. Nobody argues with you.

Alex Epstein: But we – well, yeah. But, interestingly, we have very clear data on how deadly the climate is because we can measure how many deaths are there from different climate disasters like storms and floods, extreme heat, extreme cold, etc. So, anyone remotely familiar with it, or you just think in common sense: Do more people die today from climate or a hundred years ago? If you think about it that way, it's pretty obvious they died at a higher rate a hundred years ago because they didn't have the mastery, in part because they didn't have fossil fuels.

And yet – so, think about this. Human – the climate is such that we are safer than ever from climate. We also derive more benefits than ever from climate because we can travel to nice climates, we can make them more comfortable, etc., etc., and yet people view it as the worst climate ever. Well, obviously, you're not measuring climate in human terms. How are you measuring climate? You're measuring climate on the basis of things are bad to the extent they're impacted by humans.

And so, when I – I call it the anti-impact framework because it's the idea that human impact on nature is intrinsically immoral. That's the value issue. And then, inevitably destructive. That's the assumption. And you can think of it as an anti-human religion that's focused on anti – on impact. So, basically, it says the cardinal sin – like "Thou shalt not impact nature," and then if you do, then the nature god punishes you. And you can think of global warming as it's a hell, it's the idea that we're going to hell because we sinned against nature.

And that's really the framework that – I call it the anti-impact framework which is really an anti-human framework. That's guiding so many people, including so many smart people who aren't aware of their philosophical assumptions. Or in some cases they are and they're just anti-human. But most just aren't aware. And that's what's causing them, whether they know it or not – they usually don't – to be so biased against this thing that makes the world so much better for humans because they're trained not to think of whether the world is better for humans but whether the world has been impacted by humans, and the more impact, the worse.

And my argument is, well, human impact done intelligently is essential to our well-being, what I call our flourishing. So, if you have an anti-impact framework, you have a toxic way of thinking about energy where a really good form of energy you're going to think of as evil, and that's what I argue our culture is doing.

Dan Ferris: All right. Well, eloquently put. And some people, as you did point out, I believe, are blatantly anti-human and want in fact – some people are blatant about wanting fewer humans on the planet. And they insist that we absolutely must reduce the population to a sustainable level, which is a bit absurd.

Alex Epstein: Now, some of them – now, even within that, some of them will be more pro-human than others. I know that sounds a little odd. But you can think of it as some will say "Well, I really love humans but the Earth can only handle four billion of us." It's sad, but that's some perfect number. They'll call it carrying capacity because that sounds scientific, even though you can't use carrying capacity with a productive species because there's no finite limit to carry us. But there's another kind of – but often you see – OK, if they say – they say "casually." So, I give an example of this guy Michael Mann, who's a leading climate scientist and activist on this issue.

Dan Ferris: "Scientist" in quotes.

Alex Epstein: And he just says – well, he is a scientist in a way. I mean, he's a trained scientist.

Dan Ferris: Sure.

Alex Epstein: I mean, I think he's done a lot of bad in the world. But he's – his perspective, he'll just casually say, "You know what? The world should have a billion people." And he would say, "Oh, yeah, I'm pro-human. I just want those billion people to flourish." But really, if you can casually talk about wiping out seven-eighths of the world's population, you don't seem to be driven by a love of humanity. And what you find is in the end a lot of these people, they just think humans are bad. They think we're the worst part of Earth.

So, it's like the opposite of the ancient Greek view. Sophocles, the Ode to Man, "Man is the best part of nature." No, no. It's – the perfect Earth in their view is the Earth that would exist had human beings never existed. And I think a lot of humans – I call it human racism because it's the idea that everything the human race does is bad and everything else the rest of nature does is good. I think it's – I think human racism is very – to use a popular term – institutionalized. That's the real – that's the worst racism we have today against our own species.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, Alex. I mean, this is –

Dan Ferris: Yeah, we do. I mean, the –

Corey McLaughlin: I mean, Alex, yeah, first, thanks for being here. When – you mentioned your philosophy background. I'm wondering – and you've kind of just touched on it here with going to the Greeks and whatnot – what were the catalysts for you – say, go back 10 or 15 years or whatever it may be – to arriving to this sort of framework where we're not valuing the positives in what is powering kind of the economy of the world versus intently focusing on the negatives?

Alex Epstein: Well, so for me it's – let's see, what am I? I'm 43. So, this kind of really started when I was 18 – so, 25 years ago now. Not the energy piece of it. But the philosophy piece of it was that – of course I grew up – I was born in 1980. So, I grew up in a place called Chevy Chase, Maryland. So, the East Coast, very kind of politically liberal type place, so we have a lot of environmental catastrophism, including climate catastrophism. And I think when I was 15, 16 I started to be exposed to some non-kind of political left ideas but I still had a lot of the – the Green Movement was presented very positively to me. And then, I remember when I was 18, I started getting into philosophy. And in particular, there were some students of the – or, let's say philosophers who were kind of disciples of Ayn Rand, who is a philosopher that I came to be a huge fan of. But this was before I even read her. And they were talking about this idea of "environmentalism" as anti-human.

And they had a very powerful argument that stuck with me, which was basically human beings survive and flourish by impacting nature, and this movement says that it's evil to impact nature, therefore this evil – this movement is against human survival and flourishing. And I started to see – not as well as I do now but I started to see, well, the whole idea of green means minimize or eliminate human impact. That's an anti-human idea. And part of what I learned over time is that's camouflaged because what they pretend is "Oh, we're just against the unhealthy impacts. We're just against polluting the air, polluting the water, destroying some vital species, or something like that." But that's not really it. It's – you can see they're against human impact across the board. And it's because their goal is not making the world livable for humans, at least the core of the movement isn't. It's making the world as dehumanized as possible.

So, in fact, the alleged opposition to pollution is just incidental. They don't really care – they don't care if our impact is good for us or bad for us. They think as long as we're impacting it, it's bad. They just know "Oh, if you want to get these humans onboard with this anti-human idea, pretend you only want to clean up their environment. Don't pretend you want to clean up nature of them." There's this expression sometimes "You're the carbon they want to reduce." And that's – that is sort of – you're the impact they want to reduce. You're the species they want to reduce.

So, I got this idea and I got – it was really powerful and it made me have a negative moral feeling toward a lot of the greens, which was very helpful, but I still wasn't at all – I still had no real positive feeling about fossil fuels and I still wasn't – I still – climate catastrophism was still scary to me. I didn't know how to think about it. And that really came nine years later when I started learning something about energy and fossil fuels and I started realizing "Wow, people aren't thinking about the benefits of this. And there are real benefits." Because before, you don't – either you don't think about the benefits of energy or you just assume, "Oh, solar and wind, they're probably just as good." And then you think "Oh, wait," and we go into why. But they're nowhere close to being able to provide energy that's affordable, reliable, powering every type of machine for billions of people in thousands of places.

And so, there are unique benefits to fossil fuels, which means there are unique harms from opposing them, and why isn't anyone thinking about them? And then I started to learn "Wait, there are all these climate-related benefits too and we're actually safer than ever from climate." And then, that really woke me up. And I thought "Well, this would be a really valuable thing to do, would be to change the thinking about this fundamental thing." Because I think of it as energy is the industry that powers every other industry. The lower cost energy is, the lower cost everything is. So, if you could improve the thinking about this huge lever in the world, that would be really good. And if you let it go the way it was going, that would be bad. So, I found that very motivating.

Dan Ferris: Alex, I applaud the mission that you're on there. You remind me of a book by Ayn Rand called Anthem. Did you read Anthem?

Alex Epstein: Oh, yeah.

Dan Ferris: Yeah.

Alex Epstein: Yes, I've read Anthem.

Dan Ferris: That guy, he had a very positive thing to offer his society too. They didn't take it very well.

Alex Epstein: Fortunately, our society takes mine better than he got. We're not quite at the level of we have the council and they destroy you for rediscovering the lightbulb. Not true in the plot but –

Dan Ferris: Right. They're not throwing you in prison but they're –

Alex Epstein: No.

Dan Ferris: Let me ask you the question, then. I'll put it to you as a question. I know – I was looking around on your websites and things and you do work with various lawmakers and politicians. What kind of an impact, then, are you having there? How do you assess your impact? Maybe you don't really know but how do you assess it?

Alex Epstein: So, I – in politics in particular it's been surprisingly positive. I mean, but keep in mind I've been at this 17 years now. And one thing I think I'm – is a strength of mine is, to use the term in a different context, adapting. And not adapting like my environment is changing, but figuring out how to create the results that I want to create. And so, one thing we found really, really useful in politics, and this is now – I have a pretty significant team – starting in 2020 was the way to have an impact and to help – to get more allies who would say and do the right things was to make it really easy for politicians who were inclined, who were pro-freedom in one way or another, to say and do the right thing. So, we created something and people can access a lot of it for free at the website EnergyTalkingPoints.com, or we have a newsletter at AlexEpstein.Substack.com. And the idea was take all of these issues we're talking about and break them down into Twitter-length talking points so that in any given situation any politician would know "Here's exactly what to say about it."

And we found that that was really helpful versus if I just hand them the book and said, "Hey, apply this." That's a lot of homework for somebody. But if I can say, "Hey, you can just search our website and if something comes up about fracking or climate, you can probably find it." And then, on top of that we added basically a free consulting service for major elected officials where they could text me or somebody else on our team and just ask if they have a question, which now happens all the time. And now we have something people can see at – I guess if you go to our Substack you can learn about it. It's called Alex AI. So, there's an AI now that answers – we've invested a lot in that answers questions directly as we – remind me afterward... I'll send you guys a free lifetime access to it. It's pretty fun.

So, what I've found is that by turning my ideas into a very usable, powerful form that saves people time, that saves allies time, it's increased the utilization. And in fact, the next step is – so, now we have 200 major political offices – U.S. Senate, U.S. House, and governors offices – using our stuff. I directly interface with probably 75 to 80 major politicians just myself. And I was doing none of this before so it's kind of – we cracked the – we already had all the ideas fortunately but we really cracked the code on how to do it and now we're doing that on policy. So, if there's a new administration we're going to have – in collaboration with some others we're going to have some really good ready-to-go policies that "Hey, if you want to fix nuclear, here's what to do. If you want to fix the EPA, here's what to do. If you want to fix the grid, here's what to do." And nobody – I have no power over anyone but I have the power to create – along with my team to create really good stuff and to make it really easy to use and that seems to be enough.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Yeah, that's all you can do. You can lead them to water but you can't make them drink. I understand that.

Alex Epstein: But if it's really good water, they will often drink.

Dan Ferris: That's right.

Corey McLaughlin: Hey, I've got to ask: What are the most common texts or questions you're getting right now from the members of Congress?

Alex Epstein: Well, it's often very specific to what they're doing. So, I'll just give you categories. So, one is "We have a hearing with X major official. What should I ask them? So, that's one I've been having fun with a lot lately because I – I'm not going to share my technique because I don't want to ruin it for everyone. But I think I have really good ways of asking bad elected officials questions that you can kind of make it really hard for them to weasel out of, because I've done a lot of testimony myself and I'm very – I would say I'm quite good at – I'm quite good at being the person asked the questions. But I'm telling the truth. The people – I hate it when people who aren't telling the truth weasel out of it. So, there are ways you can ask questions to weasel out.

So, one thing is helping them with questions. A lot of times they ask for fact checks. They're like "Hey, I'm considering tweeting this out. Is this true?" And then, half the time it's not true. Because even on the good side of things people spread stuff that's not true all the time. So, there's often – a very common one is "Oh, here's an argument from the other side. What about this?" Sometimes it's more aspirational. "Hey, let's – I want to work on a policy on something." So, just all kinds of things. Whatever they need.

But fortunately because – it's not very hard to do because we're just thinking about this stuff all the time. So, and if – so, it's not – it's – I'm glad they reach out and we can handle even more of it.

Dan Ferris: All right. I'm glad we talked about that. It's nice to hear somebody – it's nice to hear that politicians actually want to hear from somebody like you. And I just want –

Alex Epstein: So far, so good.

Dan Ferris: So far, so good. That's right. As long as they're still hitting the e-mail and ringing the phone, right? But there's one thing I'm too curious about here. Laying all your cards on the table then, telling the truth about your view here, where do you come down on the issue of climate? For myself –

Alex Epstein: I thought you were going to ask a way more provocative question.

Dan Ferris: No, no, no. No, no, no. I mean, well, believe it or not, to –

Alex Epstein: You can ask anything, by the way. I was just – it's funny – it's just funny because that's like – that's something I talk about constantly.

Dan Ferris: Right. For you that's a softball. But I didn't – I've been focusing solely on your fossil fuel advocacy and your ideas about human flourishing and the benefits of fossil fuels, etc., etc., and the unnaturally livable plane that we live on, which is amazing, by the way. But I'm just curious, the issue has to come up even though you are primarily a fossil fuel advocate, it seems to me: What are your views on that? Do you think we're really headed for some kind of a climate emergency or not?

Alex Epstein: Well, I would definitely not think of myself primarily as a fossil fuel advocate. I'd say I'm an energy freedom advocate, so I want the freedom to produce and use all forms of energy so long as you're avoiding unreasonable endangerment of people and that kind of thing. And I'm a fossil fuel advocate mainly because fossil fuels are being oppressed and that's the number one way in which we're doing damage to energy freedom and as a result human life. I mean, I'm a huge nuclear advocate and in terms of fundamentals in a sense that I like nuclear more than fossil fuels. I mean, it has certain attributes that are more exciting. But – and I work a lot on nuclear issues and I'm working a lot on them now. But fossil fuels is the most existential thing. The war on fossil fuels is one of the most high-leverage things in the world right now in terms of destruction. So, I happen to be a fossil fuel advocate because of the current economics of fossil fuels –

Dan Ferris: Understood.

Alex Epstein: – and because of the current immoral opposition to fossil fuels.

In terms of climate, I mean, a lot of what I've already said shapes my view because basically I think that – I'll start off with – let's say – let's talk about what's happened so far and then let's use that as a jumping off point to talk about the future. Because I always think if you can't acknowledge the present, you can't predict the future. And most people don't even acknowledge the present.

So, the present reality is that we're currently in a climate renaissance. So, currently, at this moment the climate has never been more livable for human beings, mostly because our level of mastery has far, far outpaced any kinds of challenges. If you take today's climate system and our ability to deal with it versus a hundred years ago, there's just no comparison at all. The death rate – I've mentioned this – I don't know if I've mentioned it today but the death rate from climate disasters has fallen by a factor of 50 over the last hundred years. So – and this is important because people claim we're in a crisis now. And I'm like, "If you think we're in a crisis now, you're not measuring it in human terms. You just…"

So, I always want to – when we're making predictions I want to know how – what's your yardstick? What's your I call it standard of evaluation? I think the main thing is people are just treating climate impact as intrinsically bad, so they think if we've have had an impact, that must be bad. Whereas, my view is impact can be good or bad. The main thing is our overall effect should be good, and our overall effect on climate has been amazingly good.

So, then the question is: What do we know about mastery and what do we know about climate science that can inform the future? So, we know about mastery. It's really easy for mastery, like building sturdy buildings and storm warning systems, irrigation, heating and cooling. The mastery we have now is already very capable. We also know that down the line there's good evidence – people are afraid of this, but I think fundamentally it's a good thing – we'll be able to warm and cool the Earth at will in the future. I think it's pretty straightforward that we'll be able to do both of those. Certainly cooling we know how to do pretty well already. I mean, volcanos erupt and it cools the Earth. You can inject – they've done what are called geoengineering experiments, which is a little bit of a scary-sounding way of doing it but – of talking about it, but bottom line, our mastery is going to increase in many, many different kinds of ways.

And you can be concerned about we'll use that mastery in negative ways, just like any technology you can be concerned about. But what that shows you is our ability to deal with any problems natural or manmade is going to increase. And it could increase rapidly. So, in that context, in terms of what are going to be the future climate side effects of fossil fuels, to be really concerned they would need to be a total difference in kind from what we've experienced the last hundred years. We've already been putting a bunch of CO2 in the atmosphere. We've been running this experiment and we've seen that it's warmed about a degree Celsius, two degrees Fahrenheit. And so, we don't know how much of that comes from fossil fuels but let's say all of it comes from fossil fuels. Even there, mainstream climate science says that the greenhouse effect is a logarithmic or diminishing effect. So, what it means is as you add more CO2 the CO2 diminishes in its warming power. So, you get diminishing returns. It's not an acceleration. And this is why we used to have 10 times more CO2... the planet didn't burn up because, again, CO2 gets weaker over time as you add more of it to the atmosphere. So, the warming tends to level off.

And then, in terms of – so, the warming isn't really that scary. It basically means the planet – and the warming occurs more in cold places. It occurs more at night. It occurs more in winter. So, basically, it means the planet slowly becomes more tropical. And then, in terms of storms, there's not much that definitive, but maybe it'll increase some in intensity but not that significantly.

And then, sea levels would be the main thing to be concerned about. And that – they're rising really slowly. So, they're rising about a foot a century right now. Extreme projections are three feet a century. Even that you could deal with pretty straightforwardly.

So, I think what we find is that the – even mainstream climate science, if you put it in context, which is what people aren't doing, if you put it in the context of our climate mastery from fossil fuels and the other benefits from fossil fuels, then you don't become that scared about the issue or even that interested in the issue. Because the real thing is – it's kind of like – if you're concerned about any threat, including climate, what you want to do is maximize your capabilities to society. Just like if there's a new COVID that's five times worse, the main thing is you want to have as robust an economy as possible so that you can deal with it and you can be wealthy. So – it's so crazy to think "We might have a climate problem so let's get really poor to prepare ourselves."

Dan Ferris: Yeah. That's right. There's the – there's a popular meme about people sitting in a cave wearing caveman furs and things and they say, "Well, we're at net zero. What do we do now?" So, it's sort of –

Alex Epstein: Well, that's the point. One way of thinking about it is – I talk a lot about poorer areas, including Africa, which has the most energy poverty in the world, and they'll say, "Hey, Namibia needs to commit to net zero." And I'm like "No, that's the problem, is they're already close to net zero. They need to get away from –" And if you've noticed, by the way, that net zero is the worshipping of no impact, so it's saying our number one goal should be to be a zero. That's not a pro-human view. Who wants for their kids "My goal in life is for you to be net zero"?

Dan Ferris: Yeah, but Alex, do most people not kind of sense this? I mean, I don't really know anybody – I see a few people around who are – maybe they've got solar panels on their roof and they're driving a Prius or something or an electric car or something, but most people, don't they just kind of get on with it and they sort of sense that it just doesn't really – it doesn't fly?

Alex Epstein: I wouldn't put it – there's something to that and I think something that's not quite right about that. I mean, what's not quite right about that is the goal of rapidly eliminating fossil fuels, which usually goes under net zero or carbon neutral, that's become politically popular or at least acceptable enough where that's literally the number one political goal in the world right now. Nations have all basically – except the United States under Trump – more or less – maybe one other in recent years – have not united – they've all united around "Let's get rid of fossil fuels." At least saying that's the moral ideal and then committing to it, whether – they won't actually do it to the degree they're doing it. But they're taking actions in that direction in many cases. So, it's not incidental to people's practical political values. It's in fact dominating practical politics.

But then, at the same time you see people don't – they act like it's nuclear war – or how people used to fear nuclear war. They act like that in their rhetoric, so they say "existential threat." Biden in particularly loves that term, "existential threat, existential threat." A threat to our existence. But they don't really live like that day to day in the same way that if you're – during the Cold War you hear "Hey, Russia has surpassed us in X," people being really scared to their core about this. That's not happening with climate. It's more of a people like to pretend that they're scared about it. But they're not actually that scared about it. And I think that's – and in part because it relates to – on some level they know this is not the biggest thing in the world. And also, we've been hearing about it for a while, and still most days – I mean, I'm in California. Still a nice day most days. We're doing pretty well.

And so, I think there's a certain amount of fatigue over it. So, that can be leveraged in terms of if you give people the understanding of what's actually going on, then they're pretty open to it. But it is important to give them that understanding, because absent that understanding, even if they don't – they're not truly obsessed with it emotionally, politically it's still dominating.

Dan Ferris: I see what you're saying. And it is a sort of – politically, it's sort of a sloppy thing that people will just say, "Yeah, but I'm for the environment, so I want to do X, Y, Z," whatever a politician says, so I do get that.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, that is interesting. I didn't think of it that way, as far as –

Dan Ferris: Maybe I'm –

Corey McLaughlin: – it is one of those huge political points that – in all elections now. It's there. But also, one of my favorite examples that comes to mind here is somebody tweeting about net zero from their iPhone, which is plugged into the wall or something. There's a loss of context here when you're using all of these things that require fossil fuels.

Alex Epstein: Well, and Apple lies – unfortunately, there's a huge amount of sanctioned dishonesty on this issue that's – we put out a piece on – you can see it on the Substack, AlexEpsteinSubstack.com, about the tech giants and AI and basically how – and I love tech giants by the way, fundamentally. I'm not at all hostile to "big tech." But I am hostile to the fact that for years most of these companies have been anti-fossil fuels and have done – have materially harmed our grid by calling for directly or indirectly the shutdown particularly of coal plants, not building enough natural gas plants or particularly natural gas infrastructure, which we need the more natural gas we're going to use.

And part of what they've done is they've claimed, "Well, we're 100% renewable." So, Apple claims to be 100% renewable. Google. Meta. And it's all lies. It's all lies. And it's a very simple thing they do at the core, which is they literally pay utilities to give them credit for other people's renewable electricity and give others blame for their nonrenewable electricity. Because everyone is on the grid. The grid, you just homogenize whatever – you don't just – you can't go on the grid and just consume the solar out of the grid. That doesn't physically happen. So, if the grid is 25% solar, which is a lot even there, but let's say it's 25% solar on average. And then, you pay – but then you pay your local utility to say, "Well, the 75% that's not solar or wind, we're going to just take that from other people's and then they're going to get the blame for your natural gas."

It's so – and the FCC allows this, which is crazy. This should just be obvious fraud in my view, and I'm working on some political stuff to change this because it's – but it's so damaging that everyone is taught to think "Oh, yeah, my iPhone, the Apple Watch is carbon-neutral. Apple is 100% renewable." It totally distorts people's view of reality because they think "Well, all these successful companies are 100% renewable, so no big deal if the country pursues a Green New Deal." No, they're not 100% renewable. If they tried to be, they would immediately collapse and you would never have an iPhone again. So, let's beware of this idea.

Dan Ferris: Right. Not to mention, if we go a level deeper, the whole idea of renewability itself is – it's phony. There is no renewability. I mean, the sun will burn out one day in a billion, billion years. I mean –

Alex Epstein: Well, that's a very philosophical point, which is an important one because it's – yeah, and even a more even near-term thing is all these components of these things are not "renewable." So, if you're looking at an –

Dan Ferris: Or solar cells and wind – yeah, that's right.

Alex Epstein: Yeah, of course. The whole infrastructure – so, you can't look at – if you're looking at a process – this is a key idea of considering the full context – you need to look at every element of the process. You can't just say, "Oh, the sun is free... therefore solar energy is free," because the sun is not equivalent to the energy. It's just a – it's a portion, it's a component of producing the energy. And this idea of renewables also related to this anti-impact framework is this idea that, well, we only should be allowed to use things that we can use forever and then it'll never make an impact on anything. Like, we have no right to impact the Earth... we're just sort of imposters here. Everyone else can impact it, all the other species, but not us. Versus, no, no, no, the way we survive and flourish is we are taking nonrenewable – not even resources, it's actually nonrenewable raw materials, because they're not even mostly resources until we intelligently manipulate them. We're constantly figuring out how to take raw material and make it valuable. And what we constantly do is we figure out how to take things that aren't resources and make them resources. Aluminum used to be useless... now it's an incredible resource. Same for oil, same for coal, same for natural gas.

So, we should take pride in a species that we're not sustainable in the sense of living a repetitive, circular life. We're actually evolving – or even to use a dreaded word, "progressive." We progressively learn how to use the Earth in new and better ways and we should embrace that and we should be grateful to our ancestors who used all those "nonrenewable" resources because they advanced us. And our successors will be grateful because ultimately what we leave them with most of all, in addition to infrastructure, is knowledge. And the more knowledge you have about how to master the Earth, the more anything is a resource.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So, Julian Simon, the late great economist, wrote a book called The Ultimate Resource and then The Ultimate Resource 2, the ultimate resource being the thing between your ears. That's the –

Alex Epstein: Yes, exactly.

Dan Ferris: – ultimate resource. And this –

Alex Epstein: Yeah, so he was – and he was unfortunately very unappreciated –

Dan Ferris: During –

Alex Epstein: – during his life, even though he was – you can still read him now and he's very vindicated. Yeah, Ultimate Resource 2 is the more up to date. And he also recognized – he called energy the master resource, which is really a profound recognition as well. But this is the resource beneath every – of the kind of physical, nonmental resources, this is the one that makes possible every other resource, because if you have enough energy, you can make everything else.

Dan Ferris: Right. You remind me of Vaclav Smil when you talk that way. he has a great little book called How the World Really Works and he points out that modern cities, I believe he said, and I would say modern civilization is made of four materials: concrete, steel, plastics, and ammonia. And try getting any of those without a lot of fossil fuels. You need to get them at scale. And fossil fuels are the only thing you can produce that much energy with at that kind of scale, except for nuclear of course.

Alex Epstein: Yeah, he's great. By the way, he's – Vaclav is interesting because he's really great on the facts about how the world works. We do – if you read it, you might notice that we do different considerably on the philosophy. So, I think he thinks of a lot of civilization as a necessary evil and kind of – yeah, "We would like to be net zero but we can't" and stuff like that. And I think he thinks of it as more ugly and unfortunate. And I think –

[Crosstalk]

Dan Ferris: Yeah, an anti-impactor to a degree.

Alex Epstein: – they're mostly – I mean, people do ugly – yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah, you got it. You got it. So, he has a lot of that anti-impact framework but he's sort of profoundly knowledgeable about the facts and I think generally very honest, from everything I've seen – and I've read quite a bit of his stuff – about the facts. So, he's a great factual resource. But I would just – since we're talking about philosophy, I think it would be interesting – when you're – and not just him but other people – when you're reading people, ask how much are they really viewing the world from a human flourishing perspective versus an anti-human impact perspective. And I think you'll notice a lot of people, even people who are less anti-fossil fuel, have a lot of anti-humanism that they've picked up.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Where did this come from? Where did this – I mean, I remember in my days of reading Ayn Rand she really – she went all the way back to Plato but she really focused on Immanuel Kant as kind of the ultimate – one of the ultimate sort of – closer to the modern era, anti-human philosophers. Where do you think –?

Alex Epstein: I think this is the first time – one of the first – well, he's definitely related. I don't even usually bring him up because it's so – it's –

Dan Ferris: Yeah, it's –

Alex Epstein: It takes more to – but I can explain. So, I mean – well, but why not? Let's do it. We're here.

Corey McLaughlin: Dan's your guy for this.

Dan Ferris: We're here. Yeah.

Alex Epstein: So, the – one of the –

Corey McLaughlin: I said Dan's your guy for this to bring it up. So…

Alex Epstein: What's that? Good. Good. Good. Yeah, yeah. So, well, the kind of more obvious parallels people see is you can – with this idea of the delicate nurturer and human impact destroys us, you can see this in primitive religions before we understand any kind of science, where there's some understandability to we're afraid of our impact on the Earth because we don't understand how it works. So, this idea of, well, if it rains and we didn't want it to rain, or if it doesn't rain and we did want it to rain, that must be because we sinned against the Earth. So, there's that kind of perspective – now, that has no place in modern science, but unfortunately it's very big. That's a lot of the global warming, is literally we sinned against nature, versus even if there's a problem it's just that there are certain climate physics and we activated this driver, and so it has these consequences, negative and positive. And if you think they're more negative – but if you think of it very clinically you don't think of it as nature punished us or something like that. That's a very much kind of primitive religious view. So, that's part of it.

But – and then – but then there's a question of, well, why do people believe this? And why do people not just think of it as – why do they believe this despite the fact we know our impact is generally good for us? And then, why is there this hostility toward humans and toward humans benefiting? And you can look at more philosophers like Rousseau... it's more obvious where he has a hostility toward industry. You can see different people who think there's just something wrong with us using their minds.

Kant is a little bit – it's a more abstract connection but in a sense more profound. I think one of the things with Kant is he's sort of more deeply against human – now, people consider this controversial but I think ultimately it stands up. He's more deeply against human interest, self-interest and pursuit of happiness than really anyone ever. And his whole concept – this is very abbreviated, but his whole concept of morality is around the idea of duty. You do something because it is your duty to do it. And it's not you do your –

Dan Ferris: Moral imperative.

Alex Epstein: Yeah, yeah. But it's called a categorical imperative.

Dan Ferris: Categorical. Yes, thank you. I forgot.

Alex Epstein: So, you do it – but there's – so, in philosophy there's a categorical imperative, which basically means you do it because you do it and there's nothing really behind that... it's just what you have to do. Versus something called a hypothetical imperative, which is you do it because "If I do X, then I'll do Y." And with Kant it's really – so, he'll go through different scenarios. Well, why should you do your duty? Is it because even – it'll make you feel better about helping others? Which I think is a problematic justification anyway. But he'll say, "No, it's not that. And it's not because you benefit in any way. It's just because it's your duty." And I think of this as a long discussion, but I think of this as a very corrupt idea, that people should just do things when there's nothing in it for them and nothing in it for their happiness. They should just do it to do it and there's nothing behind that. I think that's very corrupting.

And it's very – it's unnecessary because what capitalism has shown us is we can all survive and prosper together. So, we don't need to sacrifice ourselves. We don't need to be miserable. We can all potentially be happy together, so why would you embrace not that? But part of it is when you have this idea of duty to some higher thing and you just obey it, it's really easy to pick up this idea of, well, let's not just sacrifice to some human collective like the Communists said... let's sacrifice to the non-human. That's even better in a sense. That's even less selfish because if you sacrifice to the humans, at least humans are benefiting. But there's some appeal if you really get Kant, like let's just sacrifice to dirt. Let's sacrifice to nothing. That's really what it amounts to, is that we're sacrificing for this god of an unimpacted Earth.

And it's not about – if you see I was on Jordan Peterson's podcast and we had an interesting discussion about this. He's – because he tends – he tended – I think maybe I moved him some on this, but he tended to think of it "No, people are – they want the Earth to be greener and more full of other life, and so why don't they like fossil fuels, because that greens the planet and stuff." And it's like it's not about the other life. It's about anti-us. So, they're not against human impact because they love the bears so much. In fact, they think it's bad if we nurture the bears and we create – they think it's bad because we did it. And Kant, I think, is really – not exactly the father but the father of the purist version of "Human self-interest is evil. You shouldn't do anything out of self-interest. Sacrifice for ultimately your duty, for – ultimately for nothing is the ideal." And I think that's – environmentalism is the pure version of it.

There's a really good essay in one of Ayn Rand's collection, which is an updated collection called Return of the Primitive. And there's something called "The Philosophy of Privation" by a guy named Peter Schwartz, who was very helpful to my thinking. And in the very beginning, if I recall correctly, he brings up Kant and he says environmentalism is essentially the pure fulfillment – the Communists couldn't even do it, even though they were influenced by Kant, by Hagel, and Marx. But the environmentalists are the pure version because it's just sacrifice for the sake of sacrifice.

So, anyway. You asked. That's my answer.

Dan Ferris: No, good answer. I'm glad we got into that. Well, look, I believe in leveraging my guests. I mean, if you're a philosophy guy from way back and – what, did you work for Kato, Ayn Rand Institute? I mean, I want to let you fly, man. I want to let you express those views in the way that's comfortable to you. So, I don't – I'm not Howard Stern. I don't want to be a shock jock arguing with people and trying to humiliate them or whatever. That style just doesn't work. So, yeah, go there.

Alex Epstein: Yeah, that would be fun in its own way. But yeah, no, it's great.

Dan Ferris: Well, yeah, for some. For some. Not for us. It's a perfect amount of time for my final question, which is the identical question for any guest no matter what the topic, financial or nonfinancial, like we're talking about today. Same question. If you've already said the answer, by all means feel free to recap it. But it's a very simple question. If you could leave our guests with a single thought today, what would it be?

Alex Epstein: Yeah. I would probably just – why not just this idea of we're obviously thinking of climate in an anti-human way. So, that's not my most fundamental thought but it's this idea of we're safer than ever from climate, we derive more benefit than ever from climate, and yet we think of climate as the worst it's ever been. So, if something is the best it's ever been for humans and we have access to that evidence and we think it's the worst it's ever been, our standard of evaluation has nothing to do with human welfare and has to be anti-human in some form. And my contention is it's this idea of human impact is evil. So, zero human impact as the standard. But I think that example is one that's hard to argue with.

So, I would – if people are skeptical of "Why do you need philosophy, why do you – could this guy be right?" – well, if everyone is measuring the thing by an anti-human standard, including many scientists, then maybe I'm right that it's not an issue of people have the facts all wrong. They have – some of the facts are wrong, but ultimately they have the goal wrong. And because they have the goal wrong they're not looking at all the relevant facts. And I'm just saying I'm going to look at climate and the Earth and everything else from a human perspective and I'm going to bring together all the relevant facts about that, including all the benefits, including climate benefits of fossil fuels, and the other people aren't doing that.

So, I'm not claiming I've got a revolutionary refutation of modern climate science. I'm claiming I have – it shouldn't be revolutionary and unfortunately it is, because it's pretty common sense – I have a revolutionary way of contextualizing climate science.

Dan Ferris: All right. Listen, Alex, thanks a lot for being here. Like I said, I've enjoyed the parts of the book that I've dipped into and I think I can recommend the book. I think I've read enough of it that I can recommend it to our listeners, Fossil Future by Alex Epstein.

Alex Epstein: Oh, yeah.

Dan Ferris: And you can get it at all the usual places, I'm sure. Thanks very much. I really enjoyed talking with you. I wish we could do it for three hours instead of just one.

Alex Epstein: Awesome, guys. Well, it was a lot of fun. Thanks for having me.

Voice over: Opinions expressed on this program are solely those of the contributor and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Stansberry Research, its parent company, or affiliates.

[End of Audio]