In This Episode

On this week's Stansberry Investor Hour, Dan and Corey are joined by their colleague Gabe Marshank. Gabe is the editor of the new Market Maven newsletter, an advisory focused on asymmetric risk-versus-reward opportunities in the stock market. He's also senior analyst on Stansberry's Investment Advisory and Commodity Supercycles.

Gabe kicks things off by describing how he got his start in finance, including discovering the world of hedge funds and working for investing legends Leon Cooperman, Steve Cohen, and David Einhorn. He shares what he learned from each investor and how those lessons have affected his current strategy. Gabe also discusses how today's financial world has changed since the 20th century, why the idea of value investing from Benjamin Graham's era is outdated, bankruptcy being capitalism's greatest tool, and what the dot-com boom tells us about future AI success stories...

We're at a particular moment in time where we are on the cusp of a huge flourishing of new industries, right? Nobody can deny that AI is going to have this absolutely transformative impact on the stock market. But if we look back to the dot-com boom... the companies that have taken the most advantage of [the Internet] didn't even exist at the peak in the stock market. And so I think we'll see much of the same in AI.

Next, Gabe dives deep on Apple. He says the company has bungled its lead on agentic AI in phones, similar to how IBM fumbled its lead with PCs. As he points out, most of the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 Index change each decade. So he's looking forward to finding what companies could replace today's big dogs. This leads Gabe to critique Microsoft and Amazon Web Services as "at risk," advise listeners not to worry about a potential AI market crash, and explain why he's looking outside of tech for opportunities today...

When I play basketball, I don't want to play against my friends. I want to play against my kids' friends because I can dunk all over them. And it's the same in the market... There is nothing that we can say about Nvidia that hasn't already been said, right? But we can look at other areas of the market... There is an S&P 493 of stocks out there that are big-cap, great companies. That, I think, is where we should be spending most of our time.

Finally, Gabe says consumer discretionary would be a good sector to investigate for future winners, as it's likely to benefit from AI transformations. He emphasizes that AI does not just mean chatbots and large language models – it's machine learning, too. Industries like onshore oil drilling have been using that technology already to improve their efficiency. Gabe then closes the show out with a conversation about copper prices and the commodity industry as a whole...

One of the things that I always look for and I love is when you see a bunch of bankruptcies in a commodity industry, because that's your sure sign the commodity's coming up... Like if you look at what happened in the coal industry, you had loads of bankruptcies and so supply came offline. And even [as] the demand continued to decline, supply declined quicker, and you had a spike in prices. I think we're seeing that in a couple of industries right now.

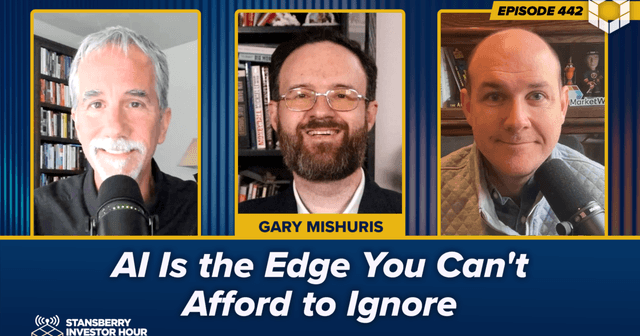

Click on the image below to watch the video interview with Gabe right now. For the audio version, click "Listen" above.

(Additional past episodes are located here.)

This Week's Guest

Gabe Marshank is the editor of the Market Maven newsletter, an advisory focused on asymmetric risk-versus-reward opportunities in the stock market. He's also a senior analyst and contributor to the Stansberry's Investment Advisory and Commodity Supercycles newsletters. Prior to joining MarketWise, Gabe spent more than 20 years on Wall Street, working directly with some of the greatest investors of all time. This includes Leon Cooperman at Omega Advisors, Steve Cohen at SAC Capital, and David Einhorn at Greenlight Capital. Gabe has been responsible for managing billions of dollars in capital and generated more than $1 billion in profits for his firms' investors.

Dan Ferris: Hello, and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm Dan Ferris. I'm the editor of Extreme Value and The Ferris Report, both published by Stansberry Research.

Corey McLaughlin: And I'm Corey McLaughlin, editor of the Stansberry Daily Digest. Today we're going to talk with Stansberry Research senior analyst Gabe Marshank.

Dan Ferris: Get out the pens and pencils. Take good notes. This guy's really smart. He's fun to talk with and he's got a lot of really good ideas. So, let's do it. Let's talk with Gabe Marshank. Let's do it right now.

Gabe, welcome to the show. Really nice to have you here today.

Gabe Marshank: Thank you very much. I'm excited to chop it up with some guys who know what they're talking about.

Dan Ferris: All right, well, we'll try to find a couple of those for you.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, is that us?

Dan Ferris: In the meantime, Corey and I will be peppering you with questions.

[Laughter]

So, I – of course, I don't know if this has become tedious for you since you've become involved with Stansberry, but I'm going to do it again, since it's just so cool to people like us. If you could tell our readers a little bit about your resume as an investor? Because it's really cool.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, no, I'm happy to talk about it. It's me. So, I went to undergraduate at Yale and most of the people in my class were interested in business, were going off to become investment bankers. And I talked to some folks who graduated and I was like, "What's that like?" And this is 1997 when I'm graduating. Investment banking was a really cool thing to do. People were making a ton of dough and everybody was miserable. They're all working their tails off, sleeping in the office, and that had no appeal to me.

So, I set out a goal to find a job in either New York or San Francisco. I'm originally from the Bay Area, so that appealed. And I wanted to make at least $25,000 a year, which sounds kind of laughable in retrospect. It is. But I got a lead on a job at a hedge fund. And at the time, nobody I knew had ever even heard of a hedge fund. And so, I had to go to the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale and look it up in the card catalog. We didn't have it online at that point. Looked in the Dewey decimal system and I found out a hedge fund was basically whatever you wanted it to be. So, I go down to New York to interview this guy. Turns out to be Lee Cooperman. Lee is famously super loyal to his employees and also tough as nails to work for. And I'm being generous when I say nails.

The interview consisted of the guy who had brought me in to interview David, bringing me to his office and saying, "Lee, here's this guy Gabe. I think he might like him." And Lee goes, "I don't got time for this. If you like him, I like him. See how cheap you can get him." And the answer was $35,000 a year. So, I was over the moon. That was 40% higher than anything I expected.

Corey McLaughlin: Oh, wow. He didn't know. Yeah.

Gabe Marshank: So, I started working in a hedge fund. But I was not doing any of the hedge-fund stuff. I was getting lunches and handing out day-end reports and basically just being the young guy on the desk. I was a week off graduation from college when I started at a hedge fund. I knew nothing.

But I'm a pretty scrappy dude. And so, first I taught myself accounting. I hadn't studied economics in college – or at least not business. I had studied economics as a political science major. And then I followed up – I started to get my CFA, taking courses on Excel, literally just teaching myself all the substrate of what you need to know to become a hedge-fund analyst because I saw these guys in their 20s making millions. And I thought like "Yeah, $35,000 is good, but a million is better. I'll take that, please."

And so, I started going around the guys and being like, "What can I do to help you out?" And first it was, "Listen to this conference call and just take some notes and let me know what the company said." And then it was, "Go to this corporate presentation at a conference and tell me what the company said." And then it was, "Call around to the sell side (that's the Wall Street banks) and get some financial models on what these analysts think the companies are going to do." And then it was, "Look at the models and start to tell me what they say and where they differ." And then all of a sudden this guy, his name was Larry, and he says, "Well, you've seen the companies. You've seen the models. What do you think?" Larry is, of course, Larry Robbins. He now runs Glenview Capital. He's a billionaire and he was my first mentor. So, he really started me in the business. And there's an old axiom, an old saying my friend has: "It's not where you work, it's who you work for." And I was really fortunate enough to work for Larry and he really taught me the ropes.

From there, I went on – and over the course of my career, I was lucky enough to spend eight years working at SAC [Capital Advisors] with Steve Cohen. I was an analyst – I was a generalist. I focused on a lot of capital intensive industries, like cyclicals, industrials, energy, utilities. But I really looked at whatever I wanted. And with SAC I was able to move to London. I was following a lot of London – European stocks. I thought there was a greater opportunity in Europe. And I moved out there and that kind of got me out of the noise and that really changed my investment framework.

And then, while I was in London, I then moved over to Greenlight Capital working for David Einhorn. David is not only a very funny dude, he is whip smart and a tremendous investor, and I've learned a tremendous amount from him as well. So, I've had the fortune to work for a bunch of these investment legends and each one of them I tried to draw something that was really going to be of value for me.

Dan Ferris: So, what – can you give us one sort of big lesson? What's the one big thing you learned from Einhorn, one big thing from Cohen, Cooperman? Was there one –?

Gabe Marshank: Yeah – look, there's so much, it's really hard to say. I asked David Einhorn at one point, I said, "What do you believe now that you don't believe five years ago?" And this is a question I think that is something I always ask myself. It's really important to have intellectual flexibility in the stock market because it's always changing. And we were going through a financial model and he looked down at it and he said, "I don't think the answer is here," pointing at the model. He said, "I think the answer is out here."

And so, I think that that numbers are the starting point. And for my entire career, I've been very, very focused on numbers. I take [Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC")] file documents as gospel. I ignore what's in investment pitch books that aren't SEC regulated. I built my models to a very high degree of sophistication, integrating with income statement, balance sheet, cash flow, and making sure they project for it. And that said, that was just a way station towards understanding the bigger picture, which is how businesses actually interact in the real world. So, that was the lesson from Einhorn.

The lesson from Steve was very different, and that was about when to know when you're onto something. And so, what I'm working with for finding ideas going forward is this instinct that I've built up after 25 years in the market of "I'm not onto something pretty big – I'm onto something huge." And I've learned to trust my instinct on that. And we say instinct, but instinct is really just a learned response after tons and tons and tons of reps. A home run hitter might have an instinct of how to swing but it's only because they've tried so many times. And so, that's what I've tried to design into my process, is that feel. Whitney Tilson likes to call it his "Spidey sense." I think you have your own version of this. Anyone with gray hair who's still around in this business is going to have their version of "Hey, this has worked for me for 25 years. I'm going to go back to that well."

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Right. For me, it's like, "I don't think this is going to be a big disaster." Because when you start – I'll tell you, Gabe, when you start in the newsletter business, you're surrounded by people pushing the most speculative sort of low-quality stuff. Every now and then, somebody hits a multibagger and the rest of them are, like, minus 50% to 100%. And getting out of that was like "Whoa, whoa. So, there's such a thing as a real business and it works like this."

Gabe Marshank: See, it's funny. We've come to – I think we probably just high-fived as we were crossing paths. So, my background was Lee Cooperman is legendarily a value investor, and so I cut my teeth on value investment. "Hey, here's a business that's going to grow a little bit more than the S&P that's trading at a little bit of a discount to the S&P and I think I can own that for a while." Or even worse, "Here's an OK business that's super cheap and maybe it goes back to being OK and investors revise that." And what I've found over time is that a small degree of winners constitutes the majority of my gains. And so, the thing that I'm training myself to do is how to just hang on to a winner. And going back to what I was saying earlier, the answer is out there, not always in the numbers. I think we've all made the mistake – my biggest investment mistakes, I can tell you, are not the ones that went to zero. They're the ones that I sold, even though I sold them at a double. I think back, even in the time I've been involved in Stansberry and its affiliates, my biggest mistakes have been cutting my gains. And that's a real Steve Cohen lesson, is how to cut your losses but let your gains go.

Dan Ferris: We did maybe high five each other. Maybe we high fived each other going the other way, but over time it's just – it's like I've lost the extreme viewpoints, it has to be all value or all this or all that. And you develop that, what Whitney called Spidey sense or whatever. It seems to me like – I feel like I've developed it about a number of things because we've had some big winners in Extreme Value and in hopefully The Ferris Report we're getting some triple-digit winners after a couple years here. And the ability to hang on to the winner, man, I don't know if those have been my biggest mistakes. Well, put it this way. You're right. They're the biggest mistakes because they would have more than amortized losers and then given you a bigger overall gain. So, I have to agree with you on that one.

Gabe Marshank: That's right. And there's no one-size-fits-all. This whole notion of value versus growth is just an asinine distinction. Value investing, buying something less than intrinsic value, you can buy a stock at 30 times earnings, but if it's growing fast enough and profitable enough, that's less than its intrinsic value. And that's fine. So, value investing often – the old version of it, the Ben Graham and David Dodd, the people in the '50s, '60s, '70s kind of grew up on, that applied to a different world. And it applied to a world – and I'm very cautious about saying when things changed, but the thing that has changed in the U.S. economy in the last 30 years is it's become less capital-intensive. It used to be to have a business you had to invest your capital in it. And so, as a result, margins were mean-reverting. If you made too much money, somebody would come in and build a new car factory or start a new airline and then that would cause oversupply and prices will come down and margins come down and then people go bankrupt, and all of a sudden there'd be less supply and prices would go up and margins would go up. And so, you get this big cycle, right?

Dan Ferris: And book value meant something. Right?

Gabe Marshank: And book value meant something. Now – and we can return to book value if you really want to get into abstruse accounting. Accounting is kind of the core of what I do, but I try not to talk about it too much because it's so tedious for most people. But the fact of the matter is that Google is not mean-reverting. Google Search is a platform that – it's not like you can start a competing search business and compete away their margins. It's not going to work that way. Same with Facebook. Same with [Amazon Web Services ("AWS")]. AWS – actually, I take that back. That's a little different. Somebody else can come in with more data centers, and that's happening. But if you look at a lot of these tech businesses and therefore the composition of the S&P, it's these businesses that have defensible margins. Not only are they defensible, they're high. Even for the companies that see competition, like a Salesforce or an Oracle, those are high margin businesses that have no capital reinvestment.

So, the difference in the composition of the economy, I think, takes this sort of fundamental belief of value investing and renders it invalid. So, we have to all be just investors. We don't get to label ourselves anymore as value or growth. It's just how do we make money and what are we comfortable with? What can we live with? Because the thing that I keep on trying to remind myself is how do I get into an investment where I'm not going to get shaken up? The analogy is you're walking through the woods and you've got to follow a path, and every once in a while, you see these trail markers. You want to set yourself up so you know the trail markers so you know that you're on the path. If you're going to get pushed around by the wind or the sun or the weather, then you don't belong on that trail in the first place. And the same way with investing. If you're going to get shaken up because the market drops 10% and your stock drops 25%, you probably don't belong there in the first place. You probably don't know why you're there.

Corey McLaughlin: Yes. And I – just going back to your comment about Dan has gray hair and he's probably got his own Spidey sense, if you have no hair like me or still relatively younger, it's probably because you're skeptical of a lot of things. At least I am. And so, that's where I – I started off in journalism and got into this that way. And I think part of the reason maybe we're all here is just kind of like independent thinking about things, is what I'm hearing from you just in terms of the approach that that you take. It's just essential, right?

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, I try to take an iconoclastic approach to how I view investments, which is just a fancy way of saying I don't care what other people think. I have been around long enough, as I said, to trust my gut, but also to have seen a lot of patterns repeat themselves. And when I look for stocks, I look for companies or industries where I say, "I've seen this movie before and I know how this movie ends." It's always the James Bond analogy for me. You go into every Bond movie. You don't know exactly who the bad guy's going to be, what the gadgets are going to be, who's going to be his love interest, but you know they're all going to be there. And you know he's going to save the world in the end. And you know that he's going to get the martini. That's what I want in my investments.

And so, I'm looking at AI today. I have the framework of what happened in shale because I think that's very, very relevant. The U.S. onshore business gives us a great framework to think about it. And what happened in – I don't want to call it dot-com, but in the telecom build-out at the end of the millennium. And these were capital-intensive build-outs of networks that had a tremendous amount of utility that enabled these new businesses and enabled this flourishing of investment. And there was huge misallocations of capital and tons of busts along the way. And that's totally OK. That's the market working effectively.

The greatest tool that capitalism has is bankruptcy. And I think that's a really weird thing to say. But I spent a lot of my time, particularly in London, focused on other markets. I've been to China 20 times because we had a huge investment focused on iron ore. And so, to understand iron ore you had to understand the country that was consuming half of the world's iron ore. So, I went there to understand the financial system, which obviously is not capital. And capitalism has bankruptcy as this wonderful self-correcting mechanism. And I've become, which is funny from a guy coming from Berkeley, California, but a huge believer in that element of capitalism that really just is this self-healing function.

Dan Ferris: Well said. No, I can probably count on one hand the number of people who have talked about bankruptcy in glowing terms like that, but it's true, isn't it? And not only that, but trying to prevent it from doing its good work is usually a mistake, a bigger mistake than most people realize.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah. And there's – look, there's limited exceptions. I don't want to completely dismiss the importance of the Troubled Asset Relief Program rescue in 2008 because it was a much larger risk looming and we can talk about that. And I think very rational people think the government shouldn't have acted and I think that's a discussion that you can have. But it's tough to make the counterfactual, or it's tough to imagine what it would have looked like had the government not stepped in. I think there's room for it. But in general, I think it's just like life itself. You've got to weed out the weaker and the stronger will go on to do better.

Dan Ferris: So, you are – so, while we're quoting Whitney Tilsen, you're a make money investor. You're just, "Get rid of my value and growth labels and I just want to make money." And we said we were high-fiving each other going the opposite direction. I was headed from speculative companies to better ones. Are you telling me you're headed from better ones to more speculative? It sounds like your evolution was not quite that. It was something else.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, again, it goes back to this notion of I've seen this before. I think we're at a particular moment in time where we are on the cusp of a huge flourishing of new industries. Nobody can deny that AI is going to have this absolutely transformative impact on the stock market. But if we look back to the dot-com boom – I'll call it dot-com for shorthand, but really it was a boom in networking that enabled Internet communication. The biggest companies to come out of it? Google at the peak of the dot-com was a private company. Facebook hadn't even been invented yet, if memory serves. And Amazon was a bookstore. So, you had the transformative technology that came in in terms of ubiquitous Internet access and the companies that have taken the most advantage of it didn't even exist at the peak in the stock market.

And so, I think we'll see much the same in AI, which is that right now we're seeing the capital-intensive part of the boom, which is giving us the substrate, the physical capacity to manage AI. But if you look at all the true success stories, they fall in two categories. They are either companies that enable businesses to operate more efficiently, or companies that enable consumers to spend their time more pleasantly. So, if you look at the companies that grew out of the dot-com boom, really you have "Software ate the world" is the axiom. There were all these software companies that enabled HR, sales, all these other corporate functions to work more effectively.

And then there's a consumer side of it. Cat videos on the Internet. Those are worth a lot. And one of the cool things about AI is that as it reduces the demand on overall labor, people are going to have more free time. It's a productivity enhancement. I know there's a bad side. People worry about the impact on jobs. But last time I checked, we were employing basically more people than we ever have in the history of the United States, so something's working right. And we're also employing them less hard. Workweeks were whittled down to 40 hours and now it seems like we might be going less. Everybody's just on a side gig these days. So, something's working right. That enables a lot of use of – more use of free time.

And the one industry we can point to definitively is the rise and rise of gaming. Hollywood was our main outlet. And I think there's only been three billion – or, sorry, three movies that made over a billion gross. There's probably a hundred games that have made over a billion gross. So, we – as we moved on to new forms of entertainment because we had more leisure time, we've created this whole new industry. And now, of course, you see the buyout of EA Sports just last week. So, I think we will find new industries. They will be AI-enhanced or AI-enabled. They may involve generative AI. I think we'll also see agentic AI. I want my own personal assistant on the phone. We're very close to that. That's coming somewhere. I don't know who will own that. Whoever owns that is going to earn another trillion dollars of market value or so.

Now, getting back to your point, that's speculative. If I come to you that I say, "Hey, look, there's this private company that is started by Jony Ive that has an investment from OpenAI and it's got this little device that's going to be your AI agent, you're like "Yeah, that's credible." But we're in a funny market cycle where some of those companies are public. And so, yeah, it's, I think, OK to speculate when the prize is so large. If you look at how the stock market is treating small modular reactor stocks in the nuclear space, I don't know if any of those companies will ultimately grab the prize, but the prize is so big that the market is just pricing in a little bit more chance that one of those companies might succeed. And what's really cool is there's this feedback loop element where if the market marks up the companies, the companies can then raise more capital to reinvest in the technology and it gives them a better shot of actually success in the end. Now, will those companies that are publicly listed be the ones that succeed? I don't know. But they're already up, like, 400% in the last year.

Again, our job is to try to make money. And so, if our money making is to say, "I bought a stock that went from 1% probability of a trillion dollar market to a 10% probability," I think that that's very valid. I think that's intellectually consistent with my framework, even if that is, to be very clear, a speculation.

Dan Ferris: OK, well said. I'm sitting here as we speak – just before we started recording, I was collecting all my – the Intelligent Speculator books, basically, Phil Carret and a few others, because I know this needs to be dealt with in the next issue of The Ferris Report. So, it's a subject near and dear to my heart right now. But you said something – we had a meeting with a lot of the editors at Stansberry and you said something really quickly one day that really grabbed my ear and I thought, "Oh, yeah." Because of course it's hard to just be this old and not have seen what happened to a lot of the capital that was invested in the dot-com boom, the TMT or whatever you want to call it. A lot of it was misallocated and a lot of it was allocated to stuff that is extremely valuable to us, like the usage went up a thousandfold and the revenues went down, like, 50% or something because it just got cheaper and cheaper. As things are more abundant, they get cheaper. It's the definition. The same thing basically. And now we see people building lots of data centers and that's the middle of the network. And you mentioned about the value creation at the edge of the network. And you just mentioned a couple instances: the consumer-facing companies that give us a more pleasant life and companies that make things easier for businesses.

Do you have any absolute favorites among those that you might want to share with us that maybe the listener isn't really familiar with, or even if they are familiar they might – you might have a different take on? If you have a different take on Alphabet, great.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, so the answer is yes and no. The answer is yes, I'm working on a couple of favorites and no, I'm not going to share them just yet. That's going to be ultimately for subscribers, I think.

Dan Ferris: Sure.

Gabe Marshank: But let's start with the framework. OK? Apple has created this wonderful ecosystem, as it always like to call it, where I think the most important part that Apple has gotten right is that its users trust it. So, I would say it is in the pole position to dominate agentic AI. And when I say agentic AI, I want to be able to pick up my phone and say, "Hey, can you look up for me on Kayak what the cheapest flights are that get me in and out of London, and then put together an itinerary of hotels I'd like? And I want you to focus on some restaurants" and so on and so forth. You can't do that today, but there's no reason you shouldn't be able to do that. We just haven't quite gotten it all meshed together. Because you can do that essentially on the large language models – ChatGPT or Perplexity, or any of those. What you don't have is one of those that's embedded in your phone that will be able to look at all of your apps.

And the reason that matters is because there's a difference in privacy. When I put that out on ChatGPT, they own it. If I do it on my phone, I own it. And that enables me to do a lot more important things. Top of list is commerce. I'm not going to put my credit-card data on ChatGPT. They own that. But if I do that on my phone and I trust who's managing the privacy, then all of a sudden I've gotten a personal assistant in my pocket. Now, Apple's in the lead and they have so far totally bungled it. Siri is a very poor product. It is the least good of the chatbots. So, they are sitting in pole position and they might fumble it.

And you know what else has done that? Lots of tech companies. IBM and mainframes, they couldn't make the transition to PCs. Eastman Kodak was the leader in digital photography. If you go up to Rochester, you'll just see a couple of empty buildings they used to be in. The list is longer than you can imagine of all these companies that led in technologies and fumbled their lead. In fact, I would say it's actually been very unusual that a company like Amazon was able to pivot from e-commerce to AWS and hold its lead, that Netflix was able to pivot from physical DVDs to online –

Dan Ferris: Exactly. I was going to say isn't that the rule, though? That failure to make that enormous change, like IBM from mainframe to – isn't that sort of the rule?

Gabe Marshank: It's – historically, it's the rule. And I think we're sitting on a lot of exceptions that probably skew investors' views of how successful the incumbents are going to be. If you go back and look at the history of the S&P and look at the top 10 stocks by market value every decade, they change, like, five to seven of the stocks every decade. It would be unprecedented if five of the – or seven of the top 10 today were still in that spot in 10 years. And so we can look backwards at the success stories, but the question is – sorry, Alphabet, Google... sorry, Apple – what's next?

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Yeah, that – Rob –

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, with Apple I keep thinking what number – with Apple I keep thinking what number iPhone can we go up to before things – before – what do they have unique and new that's coming out?

Dan Ferris: We're on 17.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, I remember years ago – if you recall the Onion, the satire newspaper, I remember getting it was actually a newspaper, that's how old I am, and it was after Gillette had released its three-bladed razor, its Mach 3, and it was a supposed interview with the head of Gillette and they go "Screw this, we're going to six blades." And now there's a six-blade razor out there.

Corey McLaughlin: Exactly, yeah.

Gabe Marshank: It's like, to your point, Corey, how far can you go? I think that kind of misses the question, though. Apple will change its form factor. It's going to go to a folding phone pretty soon. "Great. Oh, that's cool." That's still just a phone. I don't want to be on a phone. I don't think any of us really want to be typing on a phone anymore. I want to speak to something. Now, what that form factor winds up being – a form factor is just a technical way of saying how it looks. If that's a little block this big, they've gone little pins – obviously, Meta has the glasses. I don't know. Honestly, I think any of those are plausible. It's going to follow the function of it. And so, the question is what is going to be the device that enables the consumer to have an AI agent that it owns and is private and is personal? Apple has that possibility, but so far there's no – there's nothing to suggest that they're going to be able to convert it, other than the fact that they did it once before when they moved from PCs to the iPhone, but that was under a guy named Steve Jobs who's not with us anymore.

Dan Ferris: So, if I wanted to extrapolate from what you've just told me, once again, even though it seems more – even though the businesses that are there just seem utterly dominant, the top 10 S&P 500 or whatever you want to use, even though once again it seems like they are just unbeatable, unassailable, it sounds like, no, historically speaking, we still – things aren't that different and we shouldn't expect them to all be there necessarily 10 years from now.

Gabe Marshank: That's correct. And you've kind of got to take it piece by piece. So, Microsoft, I'll be candid, I'm not that familiar with. I've always found it a fairly boring business, but they've got this operating system at the heart of basically most PCs on the planet. And that's a great business. But a lot of their growth has come from cloud. And cloud is essentially a commodity business. With all of this money that's getting ported to data centers one would expect pressure on pricing. And –

Dan Ferris: Yeah, it's fiber cable. It's the same thing. Yeah. Exactly.

Gabe Marshank: So far, data growth has exceeded pricing pressure because of new capacity. At some point that breaks and all of a sudden we're going to go to – people will be talking about breakeven costs for a data center. And my guess is that's down 70% on pricing. That also impacts AWS. Now, obviously, Amazon is trying to put in all sorts of services over and there's a lot of ad services and that's great. But it's like selling bubble gum in a convenience store, in a gas station. Sure, that adds a lot. But if your core business is pretty commodity, it's not going to be the greatest business in the world. So, those are businesses I identify as potentially at risk.

Google Search. Now, how will search function in an AI world? Lord knows Google is spending enough time. They bought DeepMind for a reason. They are trying to integrate AI into their search. So, maybe they give you a virtual tour of a city and everywhere you look it says Starbucks or Jack in the Box. Sure. Maybe. But I can't believe that Google Search will be as good a business in 10 years. And when I say Google Search, I mean the existing online PC-or-mobile-driven, looking up a listing and getting paid listing. It seems likely that that will see competition. And so, Google's got to find an outlet.

And so, really what the whole market resolves around right now is you have a half trillion dollars, I think this year of AI-related [capital expenditures ("capex")]. Will there be an ultimate return on that capex? Now, some of that capex is clearly worth zero and some of that capex is worth so much it's – and it's like they used to say about advertising. Only 50% of advertising works – the problem is you don't know which 50%. That's kind of where we are when we have these big investment bubbles.

But I would like to sidestep the question. I would like to not have to make the bet on which of the tech giants that's spending $70 billion this year is going to be the winner. I would like to know what they're spending it on. It just seems like an easier bet to make. I'd like to know the company that's going to – not just the companies that they're spending it on, because we've seen the boom and all the utility and data-center stuff. I'd like to know the companies that are going to take advantage of it. That's the real holy grail here. Let's find the next Facebook, the next Google Search. That's the way to make money.

Dan Ferris: So, the companies that are going to exploit all of the infrastructure that the hyperscalers are building.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah. Who's going to say, "I can use AI to make this consumer-friendly brand that is going to basically involve no capital. It's going to be a service to consumers. I'm just going to put myself on top of AI that's provided by somebody else but I'm going to interact with a consumer in a way that delights them and amazes them and that they're willing to pay for."

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. No, that's – it's – that's exciting to me, too. I've been thinking about that ever since I kind of said, "Hey, this kind of looks like the dot-com buildup here." And then bust. Who knows when that happens but it eventually probably will. I'll say eventually probably. And then – but who's the next AI – what's the AI company being built in somebody's dorm room right now at Harvard, like Meta was with – Facebook with Zuckerberg all those years ago. And it's interesting the way you put it. Google was just private back then. Facebook wasn't even built. I think it was 2004 when it came out. And Amazon. So, yeah, it's – that's exciting to me, too. I just wonder how do we know – where do we look if – I don't even know if these companies know it, the bigger companies that are spending know what they're doing yet outside of the data-center build-out.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, I heard – a lot of that's true, I think, because, for example, this guy Harris Kupperman that we've had – an investor we've had on the program a couple of times, he put out a piece about how they were spending X amount on data centers and it was generating X amount of revenue or something. Long story short, he got a bunch of feedback from people who are really in the business, because he's really well connected, and they were like "Your pessimistic assumption is too optimistic. None of us think we're going to make money on this. We all think we're running some kind of massive loss-leading enterprise that is going to allow us to do something else."

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, that's –

Corey McLaughlin: Well, I wasn't exactly saying that but I can see that. But that – I just don't know. I don't know. Personally, I don't know where those things are, and that's exciting.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, no, with the enterprise – yeah.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, look, I think it's – Corey, I think it's dangerous to talk about when the bust comes because that implies that a bust will come and that it has certain characteristics. I think what we have to say is that over time the market will parse which capital is efficient and which capital is inefficient. That could come all at once and be painful, or it could just be a slow process of winnowing out winners and losers. And so, I don't think we have to predict or spend any time on that prediction on how it happens. I think we have to just focus on the winners and losers. Daniel points out an interesting one. So, is Google really spending all this capex on AI knowing that it's loss-losing? They have plenty of ideas internally about how they're going to be able to monetize it. But I have plenty of ideas internally about how my daughters should approach their homework. It doesn't mean that they're going to follow them or that they will come to fruition.

Dan Ferris: Right. And they probably have – their culture being what it is, they probably have – let's just say they have a hundred ideas. Not all hundred of them are going to get attention and money. And who knows which one is right? It's like running a venture-capital portfolio. We know something huge is going to happen out of these hundred things, but pick the huge thing that's going to amortize the loss for all the rest of it – who knows what that's going to be?

Gabe Marshank: And I'm saying that that's OK.

Dan Ferris: Yes, that's how it works.

Gabe Marshank: Because I just appreciated why that was a sensible approach to be taking in today's market. So, if it's good for the goose, it's good for the Google.

Dan Ferris: Right. And on the other end of it, though, Gabe, isn't it true – if you're a retiree, let's say, and you don't – all our subscribers, our listeners, they want to actively manage some portion of their money. But let's say you don't want to. AI is going to find you the same way the Internet found you in your S&P 500 fund. It found you in this form of those six or seven of the top 10 – really eight or nine probably at this point of the top 10 names. Don't worry. It'll be there. You'll benefit. Right?

Gabe Marshank: Well, look, if you're investing passively, you're already long AI up the yin-yang. That's a technical term but –

Dan Ferris: Period.

Gabe Marshank: – tech stocks are the dominant force in the S&P. And guess what? I wouldn't have Nvidia on my own, I don't think. Well, actually, I might have. We talked about that internally. But you get the joke. You're not going to wind up long all these winners if – unless you're a passive investor. And that's cool. But if you're an active investor, you have a really easy choice to make, which is do I want to fight this battle that everyone else is fighting? I don't. When I play basketball, I don't want to play against my friends. I want to play against my kids' friends because I can dunk all over them. And it's the same in the market. We can sit and we can debate Nvidia till the cows come home. There's literally nothing we can say of interest about Nvidia. And I say this respectfully. You're a smart dude. But there's nothing that is – that we could say about Nvidia that has not already been said.

Dan Ferris: Exactly.

Gabe Marshank: But we can look at other areas of the market and say, "Hey, what about commodities with the dollar depreciating 10%? What does that mean for commodity demand?" Why are we talking about oil in an environment where we're kind of at perpetual war and the U.S. is not reinvesting in shale and yet oil is down in the 60s? Why aren't we talking about this industry or that industry or literally anything else but the most tedious conversation? Sorry, tech, but it's tech. It's all anybody talks about. And that's what gives us, I think, another huge opportunity. We can invest in big speculations in tech because things are transformative, that there is an S&P 493 of stocks out there that are big-cap, great companies that I think is where we should be spending most of our time.

Dan Ferris: Oh, yeah, big-cap, great companies. Yeah. That's the rich pond. That's the target-rich environment for everybody,

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, so the question it becomes a lot – it's easy to say that in concept. It becomes a lot more difficult when you start to pick it out one by one. So, we're looking at consumer staples, is there anything interesting in consumer staples? Well, you've got the Ozempic stuff and you've got this trend against sugar. That's a pretty tough industry. Maybe we don't want to spend our time. Consumer discretionary. Well, I think you have to have a view on what's happening to income, which means you have to have a view on jobs. That's a pretty macro bet that I don't like to take. But maybe there's some interesting stuff in consumer discretionary that's actually fueled by this AI that could change things, how people approach their spending. What is the Expedia that is AI-powered, and now we're talking about consumer discretionary spending for travel. But what's the next generation of it? That's going to be something interesting. And so on and so forth. AI will transform every industry.

I'm going to call back. So, in 2000, I was working in a fund called Pequot Capital and it was the best tech fund on the street. It was run by a really wonderful guy named Art Samberg and his partner was Dan Benton who had come over from Goldman Sachs and he was the ace analyst on consumer hardware – or, sorry, on IT hardware. He was the guy on top. And they made 100% in '99 and they were the best tech investors out there. And so, we sat down as a firm and said, "How does the Internet impact your business?" And everyone said, "Oh it's going to change. People are going to buy homes on the Internet." Twenty-five years later, it's kind of true. Kind of. Not really.

But it got to me. And I was covering cyclicals, industrials, and energy at the time. And I said, "The Internet is going to impact our lives because my companies sell widgets or they sell goo, but they're going to sell widgets or goo using the Internet." And that's very true. And it's very, I think, profound. The way that these companies have operated, they've been able to rip out costs. These guys were using faxes and hand invoices and people doing all the back office data entry and all of that is automated now. That's completely transformed their cost structure. That's what AI is going to do for businesses across the board. And so, we want to find companies that are quick to that trend, implement it well, and ultimately we want to find the companies that are able to give them the AI to do that.

Dan Ferris: And just while we're headed back in time, let's just go back a ridiculous amount of time and address the fact that every time some new technology – and right now I'm just thinking of the Luddites in the textile industry – every time some new technology comes out that is really transformative, the really big ones, everybody has the same prediction that it's going to put everybody out of work. And every time what happens? It creates this whole new sort of ecosystem of dozens and dozens of new businesses. So, yes, there is disruption. People get disrupted and people –

Gabe Marshank: Hey, Dan, how many people do you know personally that you'd consider within your circle of somebody you qualify as a friend who are farmers?

Dan Ferris: Well, I happen to know a couple, but they're farmers because they did other things and now they bought a farm because they wanted to change their lives.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, I'm not including winemakers here, buddy.

Dan Ferris: Yeah.

Gabe Marshank: But my point is 200 years ago that answer would have been 100%. Or maybe 400 years ago. You get the idea. Farming has been automated to the point where very few people are needed to do that. And that's not a bad thing. It's a good thing. It is a complete, I think, sort of – I understand the fear. And this is where the term Luddite came from. It was the – it was what, the loom in England?

Dan Ferris: It was the stocking frame. Yeah. That's right.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah. But –

Dan Ferris: Yeah, they busted stocking frames, yeah.

Gabe Marshank: Right. But really, what this has always done is it's improved people's lifestyles and it's led to more leisure time. And so, that's a – Howard Lindzon talks always about the degen economy, all the spending on crypto and gambling. And he's not wrong. When people have more time on their hands, that's what they like to do with it.

Dan Ferris: Actually, crypto is another – that may be the ultimate maybe example of what we're talking about where it's a hundred different things and then one of them is really valuable. Because there are – I think the last time I looked on CoinMarketCap.com I was like, "Is that true? Are there millions – have millions of cryptos been created up to this point?" There were 39,000 of them trading on 850 exchanges. "Is that really true?" And it's –

Corey McLaughlin: Yes, that is true.

Dan Ferris: A lot of it will wind up – yeah, it is. It is. It is. I ran it down for the recent Digest I wrote about it. And that's the way it works, as you say, Gabe. That's how it works. That's a good –

Gabe Marshank: Crypto is a – and I don't want to go too far into it because everybody has their own view. And so, it's a little bit like politics or religion. There's no point in talking about it. But I think that the focus on crypto misses the point that blockchain is a transformative innovation. And I think that people spend so much time on crypto – but again, any industry that ever has had a filing cabinet should be able to replace that with blockchain. And that to me is a fundamental change in how health care, for example, and accounting and – will do business. I think that's a tremendous value. There's really no reason that you can't use blockchain to record your housing transaction rather than to have to have title insurance. That's a really antiquated industry.

So, I think that there's all these business applications for blockchain. And note, I didn't have to mention crypto at all to make that case. So, I think a lot of industries we often forget. When people talk about AI, 95% of the time, if not more, they're talking about large language models. The fact is that machine learning was making tremendous advances before ChatGPT-3 came out and blew the world out. And it was industries like onshore oil drilling where they were using machine learning to help target their landing zones more effectively for when they did a horizontal drilling to contact most of the productive shale. That's a use for AI that is not AI. And so, I try to – in the same ways I caveat a crypto out of blockchain, I try to take – AI is generally used to describe large language models, but machine learning and other versions of artificial intelligence, I think, have tremendous productivity that don't involve you chatting with a screen.

Dan Ferris: Right. Yeah, AI is – it's like talking about – it's identical to talking about the Internet. People say, "The AI does this and AI does that" and it says – those conversations tend to say very little about specific applications that – such as the kind you just named. So –

Gabe Marshank: But there's a historical reference, which I think is useful, which is that most people's introduction to AI at this point is through ChatGPT. And some of its analogs, but really ChatGPT is kind of a shorthand for it. And I think looking back, you could say that most people's introduction to the Internet was through AOL and its analogs. But it is the entry portal. I don't know if you remember that term. You do, I'm sure. It is the portal, but ultimately that's not where the value resides. Now, the idea that OpenAI – and I'll bust on OpenAI because it's a private company so I can. I don't like to bust on public stocks because it's a more nuanced thing. But the idea that OpenAI is worth a half trillion dollars, that's a pretty astonishing fact that's coming out. They're trying to raise money currently at that valuation. That to me seems like that could be a tremendous misallocation of capital because last time I checked I'm paying for OpenAI, I use ChatGPT, and if somebody came along and offered the same product for $2 instead of $20, I'd switch in a heartbeat. I don't think there's any stickiness or pricing power in the business as constructed. That's not to say that they can't pivot, but as it is constructed, going back to what we keep saying, that's not a business.

Dan Ferris: Right.

Corey McLaughlin: No.

Dan Ferris: It's a commodity. And we know how that – we know how the price of commodities works out. Speaking of commodities, actually, now that I think of it, you mentioned oil. I've heard people talk about – and I may have been one of them, I may have said this, I can't remember now – talk about – well, I wasn't saying it myself. I was talking about people who say it. That's right. So, about copper as the new oil because all of the things that we're building now from electric cars, whatever you think of them, people seem to be – a certain amount of people seem to want to use them – to data centers and all kinds of other things that facilitate all the technological revolution that we're living through require copper. And therefore, it becomes at least as important as oil in building out this new world that is filled with this stuff.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, you hear this from time to time. You know what the new oil is?

Dan Ferris: What's that?

Gabe Marshank: Oil.

Dan Ferris: Oil, yeah.

Gabe Marshank: So, look, oil has the unique ability of being a transportable source of fuel. That's what oil really resolves down to. That is the largest use of it. But it's something like 20% of global energy consumption is transportation fuels of various stripes, which is driven by oil. The rest is stationery and those can be – use much larger power sources, whether coal, nuke, hydro, whatever. Copper is copper. I think copper is a fascinating commodity. It's called "Dr. Copper" by a lot of people in Wall Street because historically its ups and downs have predicted the economy. But the amount of copper that's going to be used in the build-out of AI, it's there, it's real, and everybody knows it. It's not so surprising but it's also not the bottleneck.

So, if we look at the infrastructure that we are trying to build out to support AI and also electric vehicles ("EVs") and everything else, but it's really AI that is the largest impact here, the bottlenecks are twofold. One is the government. So, when you build a power facility, you need to interconnect it to the grid. And to connect to the grid is, I think, around a seven-year process right now. It goes to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, FERC. It's a real pain in the ass. And actually – and I would say, actually, quite surprisingly, the administration has been making it more difficult. There was a huge power line that was just canceled. They canceled the power line to this offshore wind turbine project in Rhode Island. But the fact is that there's really no other source in the near future for power. So, I think that'll probably change because there's such insatiable power demands. That's bottleneck one.

The second main bottleneck is really in turbines. So, you can say, "Hey, I've got gas. I've got a data-center operator. I've got a PPA, which is a power purchase agreement, between the two. All the numbers stack up. Let's go." And they'll say, "Cool. We can get you the turbine that you use to run that that gas power plant in about five or six years." It's like "Well, OK, that's not great." So, that's why stocks like GE Vernova have gone through the roof. It's like stocks – so, that's GEV. If you look at Quantum Power, PWR, that's gone through the roof. They are the largest provider of interconnection build-out, and they are generally seem to be pretty good at navigating this FERC process.

That's where the real bottlenecks are. It doesn't seem at the moment that copper has a bottleneck. However, there is great demand growth. So, you shouldn't see bottom cycle sort of prices. But if you take a look at, say, lithium as an example, it's been recovering recently but you had a huge boom related to EV and then it just collapsed because you had a huge glut of supply. So, even in conditions of very strong demand, it's fine. Supply is always what matters in commodities. And that was – we did the work when I was back at Greenlight. We were short iron ore stocks because we had this sort of Venn diagram. We're like, "All right, well, China's going to grow between 5% and 7% and iron ore supply is going to grow between 11% and 14%. Even if it's the best growth of demand and the worst growth of supply, there's still going to be too much." And sure enough, pricing totally collapsed. So, I think for copper – I'm not super on top of the supply picture right now, but I don't think it's a surprise to the industry to know that there's great demand growth, which means they should be bringing the supply out.

Dan Ferris: They should. The guys at Altius Minerals did some really interesting work where at the time – it was a few years ago – they determined what they called the incentivization price, the price at which it makes economic sense to build a new copper mine. It was, like, $5 a pound. But they researched further and found that historically speaking, you need to achieve something like twice that price to really get a significant amount of capital to move in and actually increase the available supply in some amount of time. So that is what it is. But I'm glad – I just want our listeners, Gabe, to know something. What Gabe just said, if you're any kind of a commodity investor, what Gabe just said is very important. There's two things about it. You can – the supply is the important part, and it's the knowable part, the more knowable part. The other part is the part that gets everybody excited. Everybody gets excited about the demand. But if you're that kind of investor, just learn about the supply. That's where you're really – your knowledge leverages the greatest. Anyway, I'm sorry –

Gabe Marshank: Yeah, I'll take you one further than that, Dan, I think it's – it cannot be emphasized enough: Not only is supply much more knowable than demand because if you think about it, it takes a couple of years to get a copper mine on so you have good visibility.

Dan Ferris: A few.

Gabe Marshank: Right. Right. So, you have good visibility. And that's the case for any commodity. You can't just make it up out of nowhere. It takes a while to get these world-scale projects on. But also, supply varies a lot more. Demand – economists will be like, "Oh, I think the economy is going to grow 3.2%." And someone's like "Actually, it's going to grow 3.1%." And the answer is who cares? It doesn't really – it's an order of magnitude off from the changes in supply that you get. And so, I've spent my entire career focusing on the supply side. When I was back at Pequot, like I said, I was going to cyclicals, industrials, and energy. I built a spreadsheet of every auto plant in the world. So, I was like "How many Ladas are going to come off the production line in Russia this year?" And that's how we figured out what was going to happen to the pricing of pickups in the U.S. And all the money that GM was making at the time was in pickups. And so, we were able to have a view on GM, which was a good view to have. So, supply is orders of magnitude more important and knowable, and yet it's the one that nobody focuses on. It's a dream – I've always enjoyed.

Dan Ferris: It's not where the stories are.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah.

Dan Ferris: It's not where the – yeah.

Gabe Marshank: And one of the things that I always look for and I love is when you see a bunch of bankruptcies in an industry, a commodity industry, because that's your sure sign that commodities are –

Dan Ferris: Yeah, and Goldman shuts their trading desk. Those two things.

Gabe Marshank: Yeah. But if you look at what happened in the coal industry, you had loads of bankruptcies and so supply came off line, and even the demand continued to decline, supply declined quicker and you had a spike in prices. I think we're seeing that in a couple of industries right now. And I think there's an idea out there, I'm not going to disclose it here, but that I absolutely love, that that's exactly the dynamic that's happening.

Dan Ferris: Oh, OK, so we're going to find out more about this. I think October 29 is an important date that we probably need to discuss and Stansberry – and actually, everybody within the sound of my voice can learn more about it by going to stansberrysecret.com. And starting on October 29, all these things that Gabe doesn't want to tell you – and I fully – I'm highly sympathetic. I have a lot of things I can't tell you either because I have subscribers.

Gabe Marshank: We're going to be having an event and it's going to go through not just sort of the history that I'm touching on here and the investment framework but obviously most importantly is actionable ideas. As I said, I think there's loads of stocks out there that I'm super excited about and we're going to talk about one that could be a 10-bagger, if not more. I'm really focused on it – look, I'm trying to balance – I come from this background of understanding real industries and real businesses but we're at moment in time where there's an opportunity. And I don't want to overegg the cake. We always have to be careful. We always have to be thoughtful. But sometimes being careful and thoughtful means taking a little bit of a swing. And things are moving so quickly right now, I'm so excited about these opportunities that I'm seeing. I haven't been this excited about the market in a really long time.

Dan Ferris: That is great. And I have to say it has been absolutely a sheer joy and pleasure to have you on. I don't want my other guests to take this personally but I've enjoyed talking with Gabe very, very much and so much that I'm going to invite him to come back really, really soon. I usually say, "Hey, another six or 12 months, I hope you won't mind if I give you a call" but I don't want to wait that long because I'm having a hell of a good time. I don't want to stop even though it's time for us to move on to our final question. And the question is simply if you could provide them with a single takeaway today, a single idea, what would it be? And if you've already said it, feel free to repeat it.

Gabe Marshank: So, it's not going to be original, but there's a reason that this advice has lasted through the ages. It comes from the Oracle at Delphi and Greek myth. And it's "Know thyself." The biggest mistake I think that I see investors make, and I put myself at the top of the list because I've made just about every mistake out there, I've – literally over the course of my career I've lost billions of dollars. I've made billions and netted out very much ahead. But I've lost a lot of money for a lot of rich people and they were still willing to let me come back and have another crack at it.

And it came down to this: knowing what you are good at and being really rigorously honest with yourself. You invest in a stock and you think "If I get it right, will I feel vindicated or will I feel lucky? If I get it wrong, will I feel silly or will I feel unlucky?" Now, if you can be on the vindicated unlucky side of the spectrum, you're going to be a very good investor. The way to get there is to know who you are as an investor and who you are as a person. If you love the cut and thrust and the day to day, maybe you shouldn't buy a stock that's a buy and hold with a lot of volatility because you're going to get stopped out. Now, vice-versa, if you think "OK, I'm going to buy this stock and set it and forget it because I think this company is going to be dominated – going to be dominant in its space," then don't go trading stocks every day.

Figure out who you are as an investor. Be really honest with yourself about who you are and then do that. Plan the trade and then trade the plan is kind of a motto that we've had for years. And really, that comes down to knowing who you are as an investor, and honestly as a person.

Dan Ferris: Well said. And a great message. That's a – I'm glad you went back to the Oracle of Delphi and put it in your own words as well. Thanks, Gabe. It's been a real pleasure to have you here. I really enjoyed this.

Gabe Marshank: Thank you very much. It's been an honor to talk with you and let's do it again soon.

Dan Ferris: Very. Yes.

Corey McLaughlin: We'll have you back soon. Yeah, it's been great. Thanks.

Dan Ferris: Well, I meant what I said. That was a lot of fun. And before I forget, I'm going to say one more time and maybe even again before we exit today: stansberrysecret.com. You want to sign up and find out what Gabe is going to talk about on October 29. He is one of the most brilliant folks that we've ever had in the Stansberry universe. Great investor. Very smart guy. And just a great guy to listen, to talk – isn't Gabe just a great talker? Period.

Corey McLaughlin: Oh, yeah, great talker for sure. He's coming for my spot here probably. Right?

[Laughter]

But it's – he's – since he's joined us, even internally, just different things that he's done, talking to different analysts and editors and in meetings and whatnot – he did a little crash course for some of the – for everybody on different approaches, capital-intensive, et cetera, and how to identify businesses and whatnot. Yeah, he's been great. And I think you got a sense of that there even more so, and his background and what he brings to us is tremendous.

Dan Ferris: Absolutely. In fact, I would go so far as to say any conversation with Gabe about investment topics, for me at least, is always an education. I'm always the student when a guy like that starts talking.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, for sure.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So, that's why I sort of counsel people to get out their pens and pencils. I hope they did so. And having – I can't even underscore the importance of having someone around who thinks like this because I'm evolving all the time – we all are hopefully trying to do some of that – but I've recently changed a lot more. And I think guys like Gabe, they're better at changing their – they're better at evolving. For me, I've sort of – I practiced the value craft for a long time and then I practiced it on the better businesses and so forth, but now I'm really changing things and trying to understand where value is being created in AI and other kinds of technology. Quantum computing is another one that's got me kind of interested right now. So –

Corey McLaughlin: Oh, nice.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So, just – I will struggle through that and I will learn and I will grow and it will benefit my subscribers. But I've got to – I have to say it when it's true: Gabe is a step or two ahead of me on that one. And you should really listen to what he has to say on October 29. Go to stansberrysecret.com and take some good notes and listen closely. You'll have fun too listening to him talk. All right. Well –

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. He's definitely a guy that – whose work you want to be following if you're not familiar with the name in our universe. You definitely want to. Alliance members already have been getting stuff from him, but everybody else can go to that at stansberrysecret.com and check that out when that new talk comes out.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, that'll be like –

Corey McLaughlin: I'm looking forward to it.

Dan Ferris: – Gabe for everybody, instead of just for Alliance members. That's right.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah.

Dan Ferris: Well, that's another interview, and that's another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I hope you enjoyed it as much as we really, truly did.

Announcer: Opinions expressed on this program are solely those of the contributor and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Stansberry Research, its parent company, or affiliates.